In 2020, Maggs published a significant catalogue: that being, its 1500th.

The items featured in this catalogue were not arranged thematically, as per convention, but instead by their ability to captivate the particular interests of our members of staff. Each member was asked to submit one item, from the breadth of Maggs stock, which was significant to them.

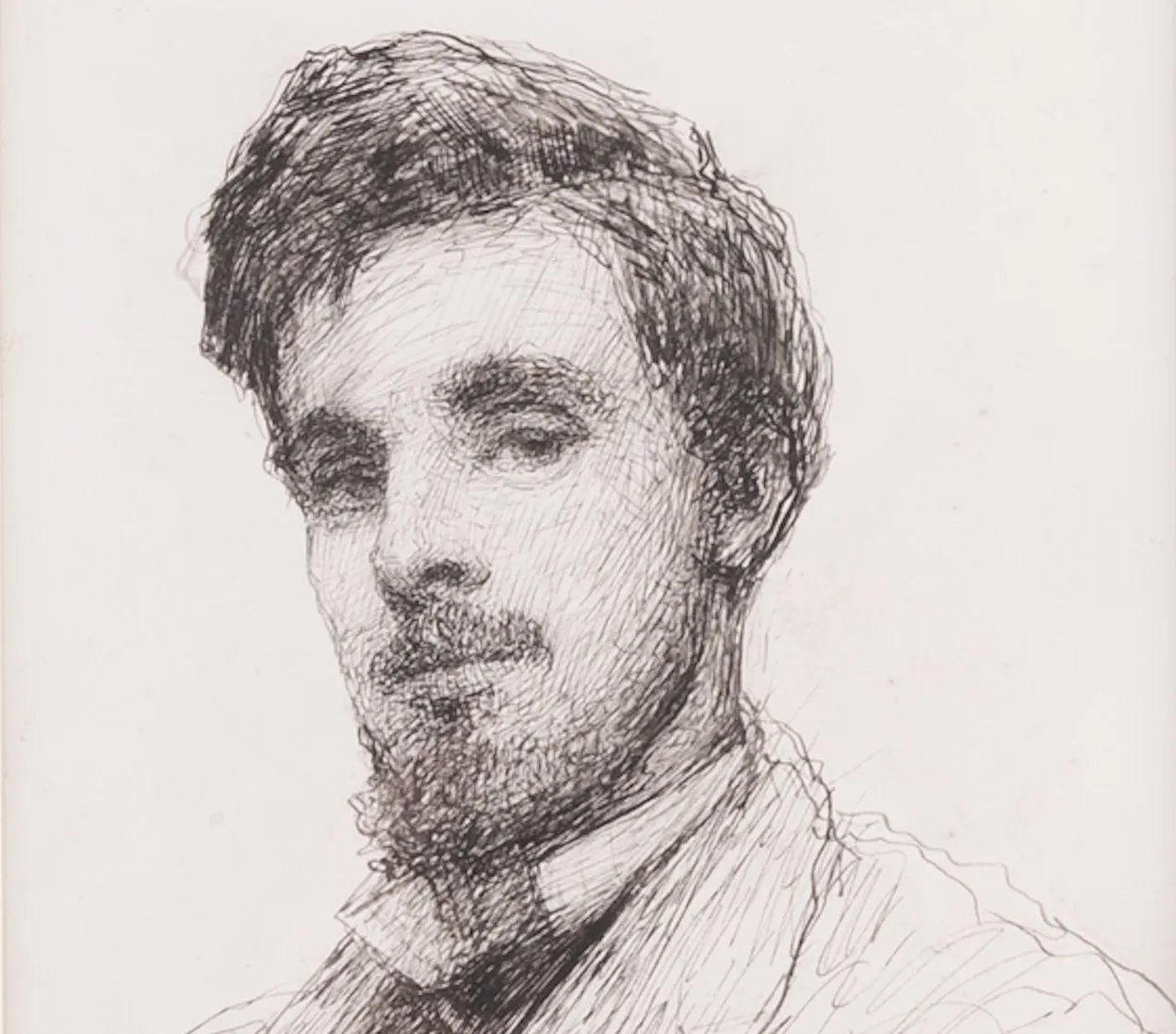

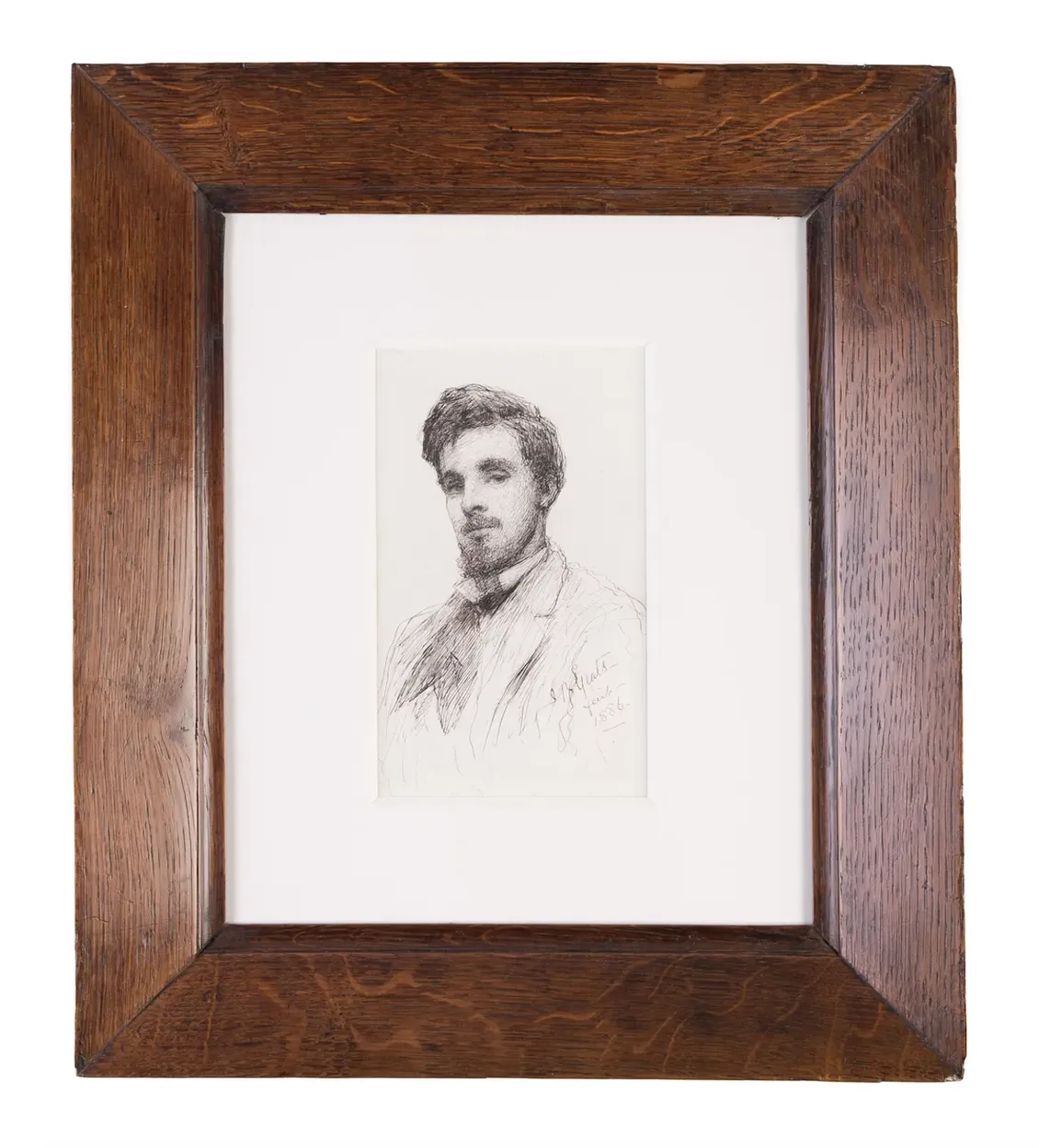

We return here to the pages of that catalogue to find the submission made by Ed Maggs. His choice was a fine portrait, in pen and ink on paper, of a young W.B. Yeats, signed “J.B. Yeats fecit 1886”.

Of this portrait, Ed wrote the following:

We booksellers often fall prey to wishful thinking and describe not the item in front of us, but what we want it to be: Ezra Pound’s copy of Prufrock would be described as if it were his copy of The Waste Land; Jane Austen’s copy of Pamela would be catalogued as if it was her Sir Charles Grandison, and Lord Byron’s copy of The Vampyre would prompt an essay on his Frankenstein. But the very best material, such as this drawing, doesn’t need this, for it provides its own points of reference and stands alone, unqualified, at the centre of its own narratives. All other portraits of WB Yeats, and especially of the young WB Yeats, have to be seen in the context of this drawing: it is the ne plus ultra.

Its historical significance is also matched by its quality as a work of art. I admire the sensitivity of its observation as the poet leans back from the viewer, not so much issuing a challenge but inviting one. Its portrayal of the estranged intimacy of the father-son relationship is also full of personal meaning for me, for I have been lucky enough to work with my family, including my father and my son, and believe that this sense of similarity and difference is at the heart of all family relationships.

I’ve also chosen this picture because I would like to sell it! Not just because it’s valuable, but because booksellers have a slightly perverse way of displaying our love for something, by selling it. As Oscar Wilde meant to say, “All men sell the thing they love”.

Yeats’ play Mosada first appeared in the Dublin University Review, and became his first book when published in October 1886, in a small edition paid for by the poet’s father, who also chose this portrait as frontispiece. The presence of a portrait of the author, for the first book of a 21 year old, drew criticism at the time as being rather portentous: Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote of it “For a young man’s pamphlet this was something too much; but you will understand a father’s feeling”, and the poet himself was still defensive about it fourteen years later, writing that “I was alarmed at the impudence of putting a portrait in my first book but my father was full of ancient and modern instances.”

It is an astonishingly eloquent drawing, announcing a great poet at the outset of his career: the poet invites the reader to challenge his arrival, and the artist affirms both the son’s genius and the father’s role in it. It distills the young poet’s single-minded oddness: “ ‘a queer youth named Yeats’ … a rare moth”; a “tall, lanky, angular youth, a gentle dreamer”; “ ‘the deference due to genius and the amusement which is the lot of the oddity.’ ” (all quotations from Murphy).

William Murphy’s biography of John Butler Yeats is tellingly titled Prodigal Father, and from a relatively early age his children had to support him emotionally and often financially. They were all notably industrious in their own lives, and it is tempting to see this as a reaction against their father’s lack of focus. He is highly regarded as a formal portraitist “by far the greatest painter that Ireland [had] produced” (Henry Lamb, quoted by Murphy), but never achieved consistent commercial success, and as he matured as an artist he found it increasingly difficult to complete work: “more and more he disregarded hands and garments, concentrating on the face; but as the face changed continually the work never ended,” (Murphy). None of these qualifications apply to his sketches and drawings which are often stronger and more evocative than his more heavily-worked oils.

In their own ways father and son were both lifelong seekers for truth. “All my life I have fancied myself just on the verge of discovering the primum mobile” wrote the father in 1914, but whereas the son was continually reinventing himself as a poet, restlessly interrogating his muse, the father was cursed to repaint and repaint. His famous self-portrait was commissioned by John Quinn in 1911, and remained unfinished at the artist’s death in 1922; the son in Reveries over Childhood and Youth told how his father “started a painting in the spring, and as the season went on added the buds and leaves to what had been bare trees, then covered them over with the rich foliage of summer, painted the green out as fall came, and ended up with a landscape of snow.” (Murphy, The Drawings of John Butler Yeats).

“In one important saving characteristic, however, [William] remained his father’s son: he would not compromise his art” (Foster), and at the end of his own life the son celebrated the father in the opening to his poem “Beautiful lofty things”, where John Butler Yeats is listed as one of his Olympians.

Beautiful lofty things: O’Leary’s noble head;

My father upon the Abbey stage, before him a raging crowd:

’This Land of Saints,’ and then as the applause died out,

’Of plaster Saints’; his beautiful mischievous head thrown back.

As foretold by his witty rephrasing of one of Wilde’s memorable quotes, Ed did, indeed, sell the thing which he had so loved. Though, just as this portrait had been cherished by Ed, we have within our current stock a portrait once treasured by W.B. Yeats himself.

Yeats' own copy of the extra large cabinet portrait of the great muse and inspiration of his life, Maud Gonne, remained in the possession of the Yeats family until 2017. In his Memoirs, Yeats alerts us to the power of his feeling for Gonne, writing: “I have never thought to see in a living woman so great beauty. It belonged to famous pictures, to poetry, to some legendary past. A complexion like the blossoms of apples and yet her face and body had the beauty of lineaments which Blake calls the highest beauty because it changes least from youth to age, and a stature so great that she seemed of a divine race".