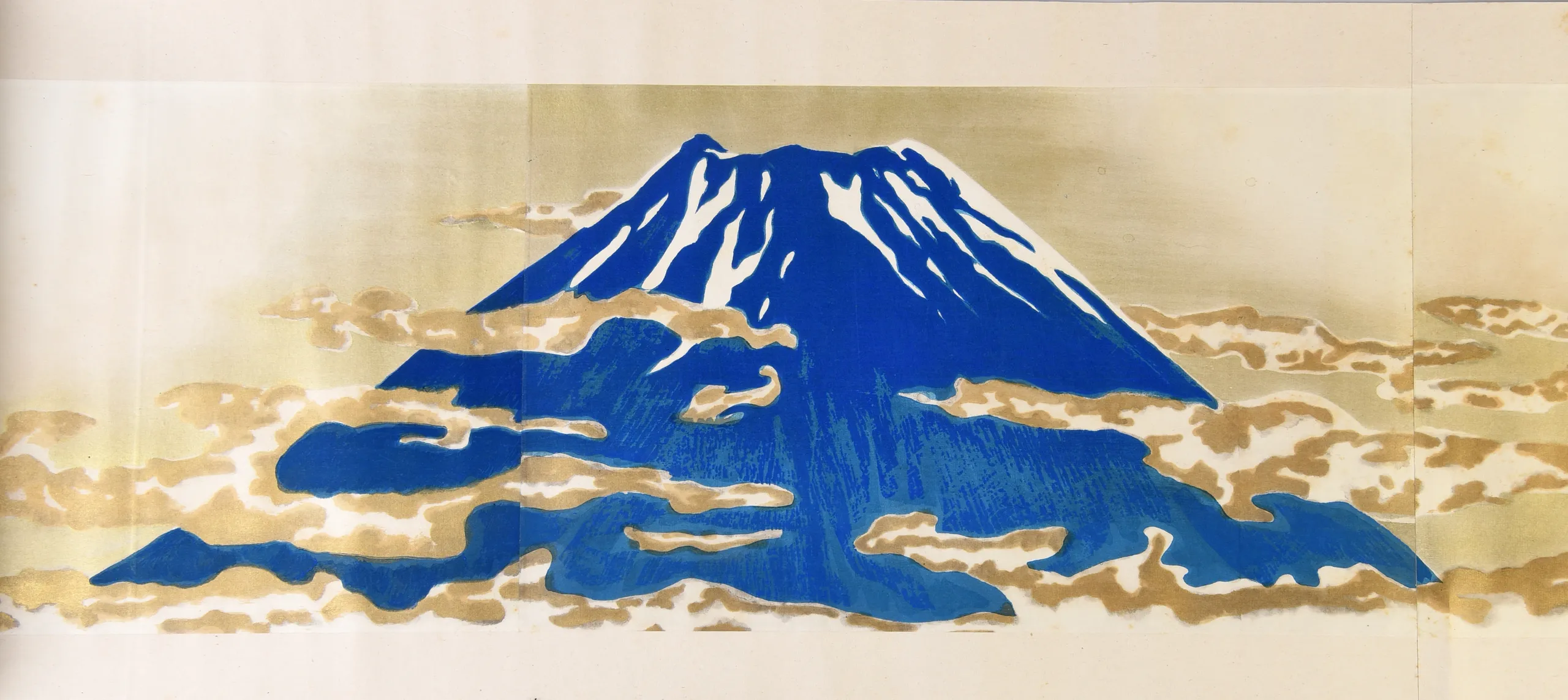

Hiroshige was born into a prestigious samurai family and served as a fire department official assigned to Edo Castle, protecting arguably the most important building in the capital city. Preferring to pursue art, he passed his title down to his son, and formally adopted the artist name Ando Hiroshige in 1812.(1) In a fantastic article about Princeton University’s collection of Toōaidō materials, curator Nicole Fabricand-Person writes, ‘Why he was included in the entourage is unknown, but it appears he was sent to make a visual record of the ceremonies and other aspects of the trip’.(2) Thus began Hiroshige’s documentation of the Tōkaidō, in the company of samurai peers and valuable horses.

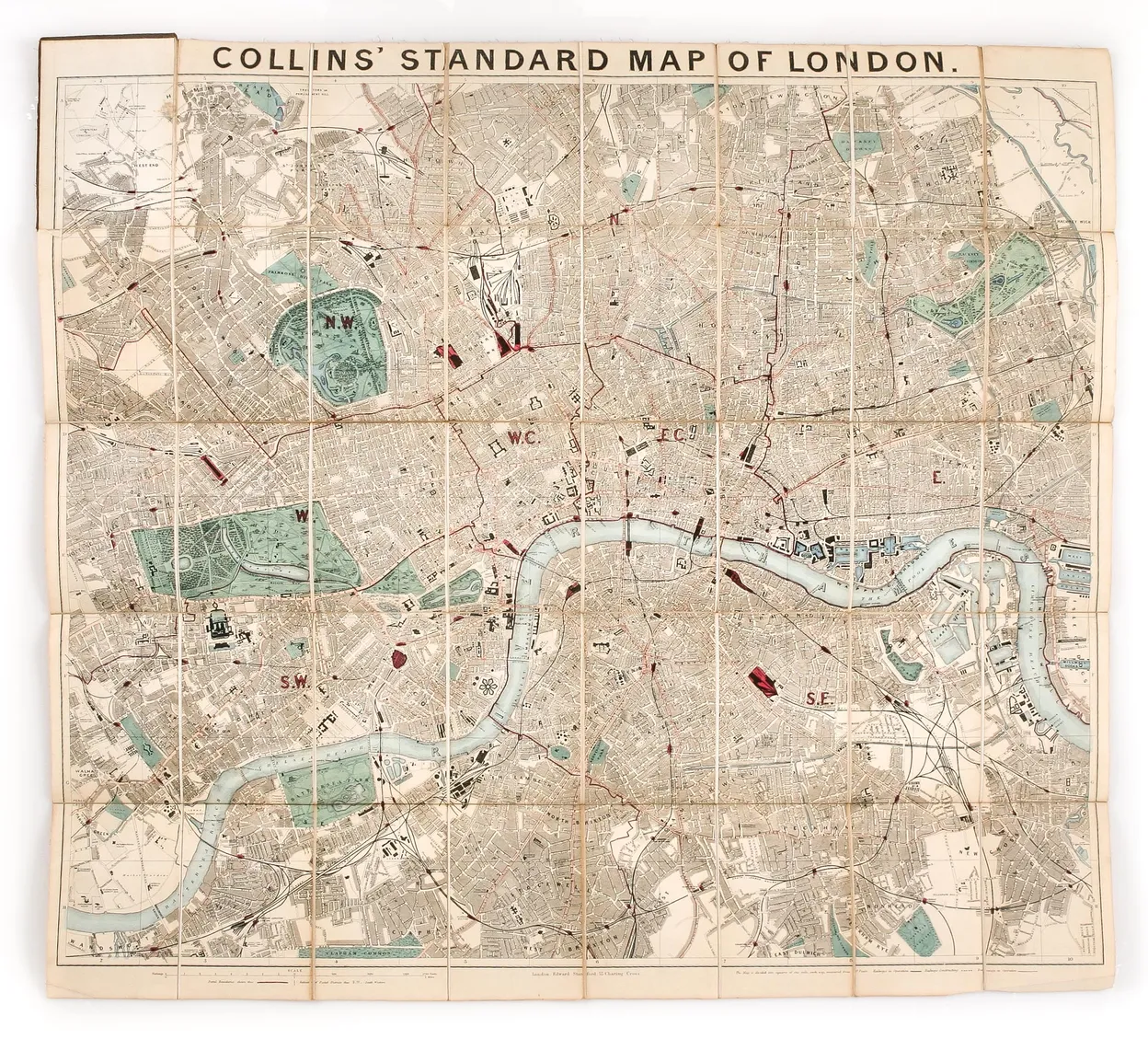

On his journey, Hiroshige would have encountered many types of people. Since the Tōkaidō connected the two most important cities – the ancient capital of Kyoto and the modern capital of Edo – it played host to all echelons of society, from high-ranking samurai to low-ranking merchants.(3) In his book on the history of Japan, diplomat and scholar George Sansom describes the heyday of these roads:

... [the gokaidō] now thronged with the retinues of daimyo passing to and from their fiefs, officials and messengers travelling to Osaka, Kyoto or other places under bakufu control, and a heterogenous crowd of merchants, pedlars, pilgrims, players and other itinerants. (4) Strung out along these main roads was a succession of townships, composed chiefly of shops and inns, eating houses and less seemly establishments to meet the needs of travellers, scenes of bustling many-coloured life which was later to be recorded by Hokusai and Hiroshige. (5)

Considering the large number of people, packhorses and palanquins moving along the Tōkaidō, at points the clamour would have been tremendous. As Sansom mentions, the main highways were not just travelled by merchants and pedlars on pilgrimages, but by samurai and their entourages, forming a true social melting pot.

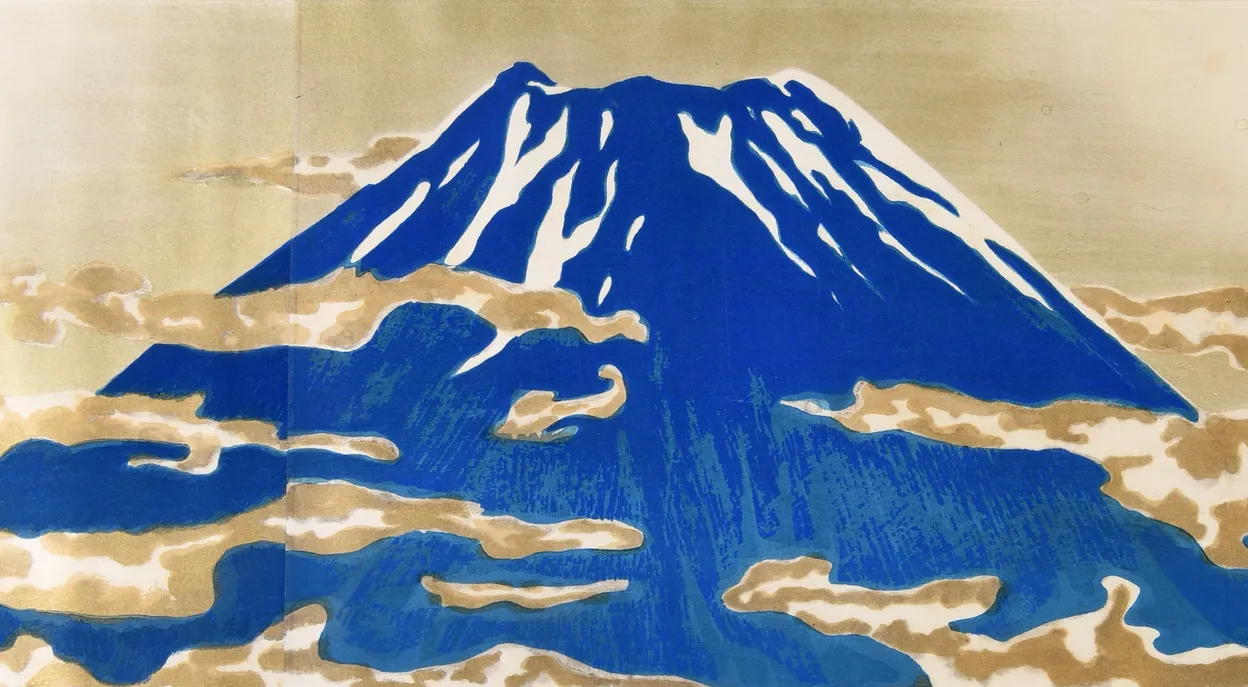

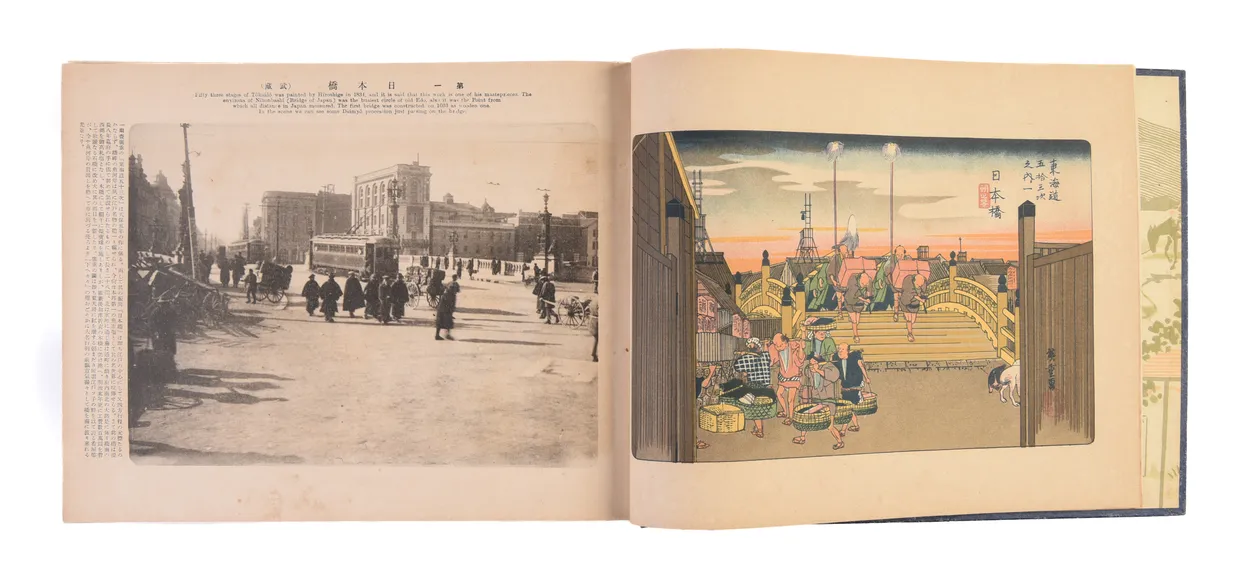

The ‘53 Stations’ refers to the shukuba, which were Government-designated resting stops on the Tōkaidō. There were inns at each shukuba – some more refined, others much cheaper for commoners – as well as shops and eateries serving local delicacies. Although Hiroshige’s series centred around the 53 official shukuba, it depicted 55 scenes in total. It is bookended by two famous bridges; in the first print we leave Edo via Nihonbashi, and in the last print we enter Kyoto over the Sanjo O ̄hachi. Both remain important landmarks today.

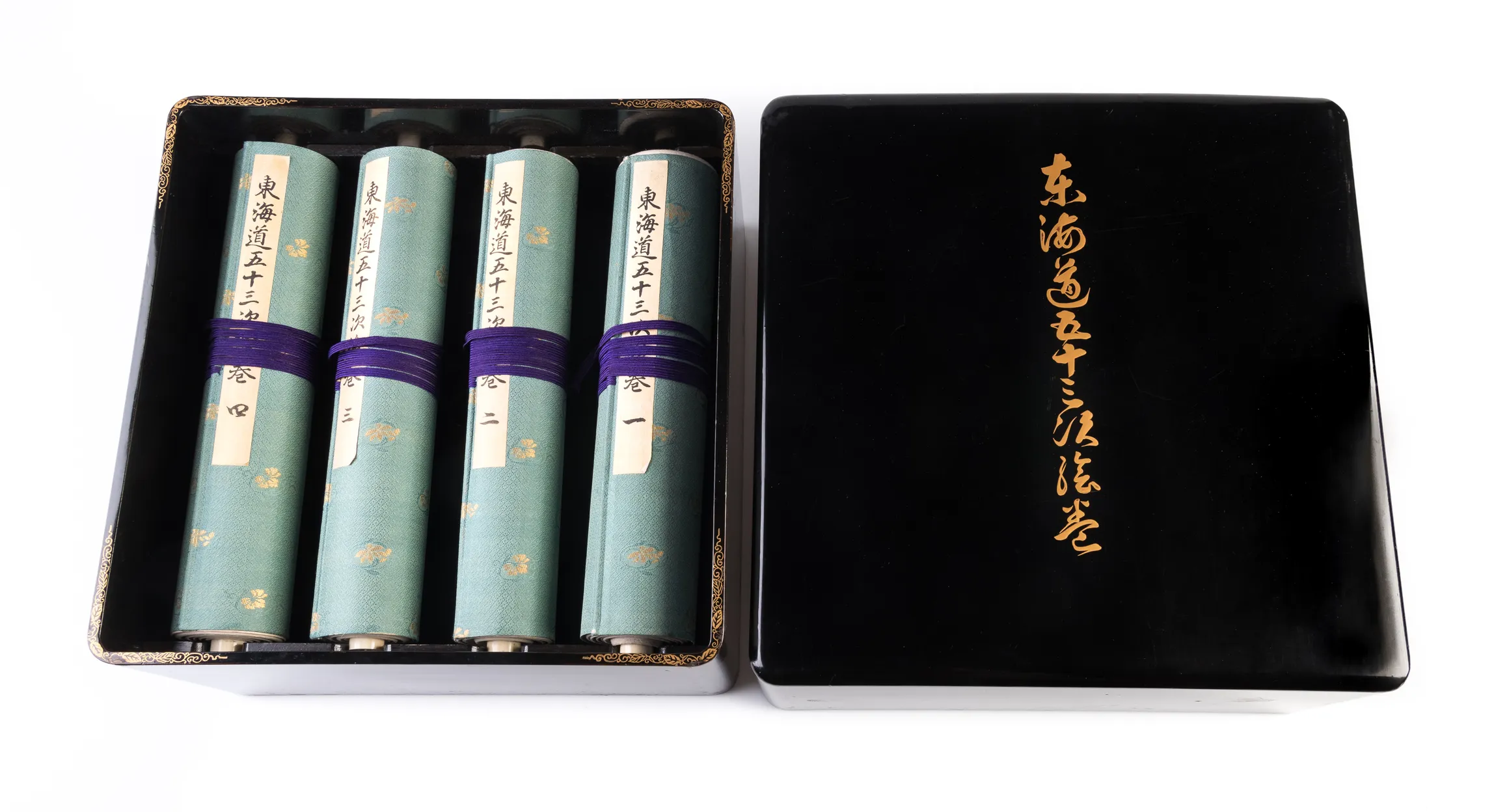

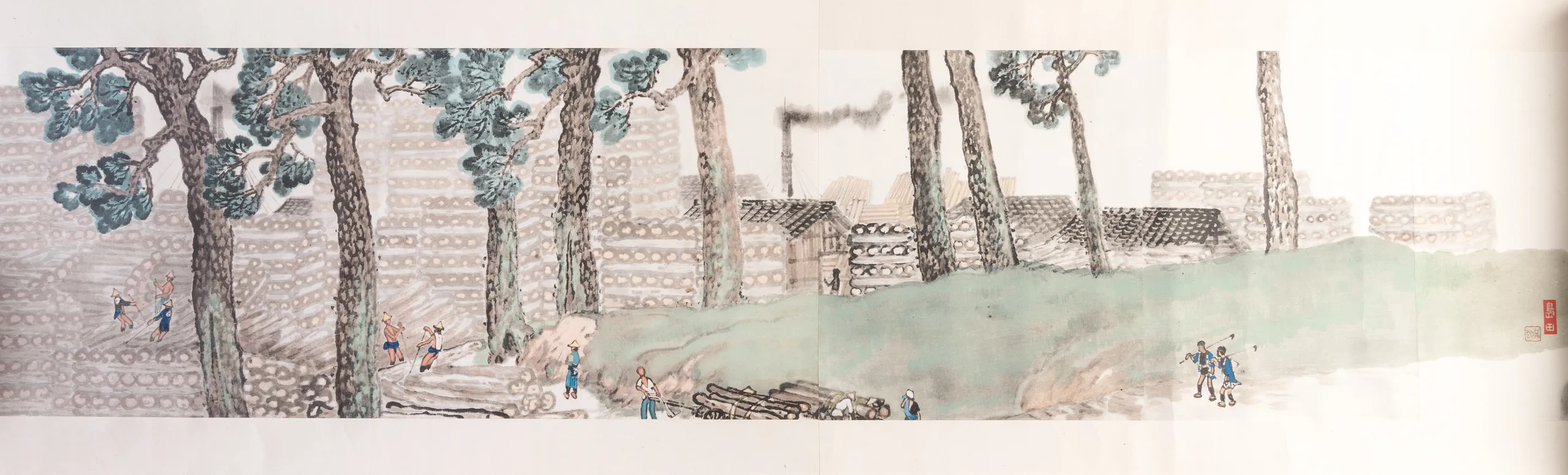

The Tōkaidō was not simply a practical route between two cities, but a journey through Japan’s dramatic landscapes with busy, strategic stops that offered entertainment and commerce. This is wonderfully captured in the Tōkaidō meisho-zue, a guidebook to the Tōkaidō in six volumes, which was first published in 1797 by Kobayashi Shinbe. The book is laden with highly detailed woodblock-printed illustrations. While some depict panoramic views of the countryside, others show close-ups of busy street scenes. Such is the intricacy of the meisho-zue that they continue to be invaluable resources for researchers of early modern Japan.

Readers of the sixth volume of the Tōkaidō meisho-zue, will note that it shows Izumiya and its neighbouring shop Masuya, both publishers and booksellers who produced a vast number of prints and publications (vol. 6, ff. 73r–74v). Looking closer, one can identify individual prints of famous landscapes and kabuki actors. Outside the shops, wandering bibliophiles stop to peer inside...

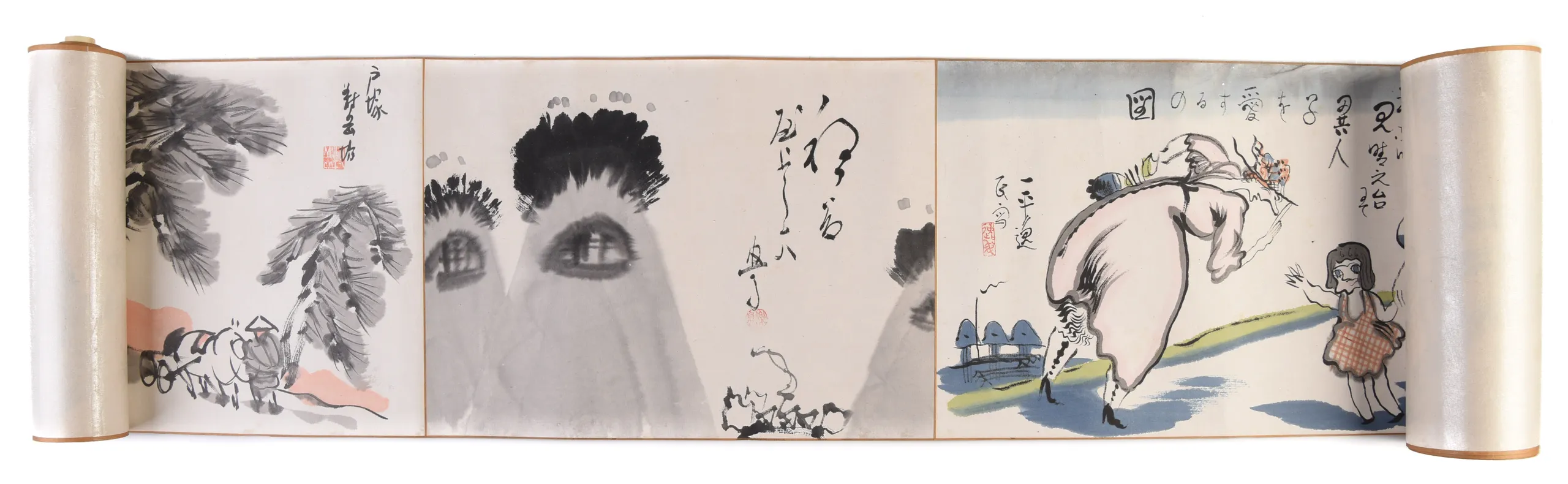

The meisho-zue undoubtedly influenced Hiroshige, as did a number of literary and illustrated books published on the theme of the famous highroads. However, it was Hiroshige’s sensational series that proved to be the most enduring representation of the Tōkaidō. Indeed, owing to the success of the first series, Hiroshige continued to make over twenty variations.(6) While some show different activities taking place at each station, in others Hiroshige changed the composition entirely. Dansendō published the harimaze edition of the Tōkaidō, wherein each print was designed vertically and featured a cluster of three to six vignettes of poetry, local craft and delicacies, as well as elements of scenery.(7) Around the same time, Shōrindō published a version in which each station was represented by a different local beauty.(8) Hiroshige was the master of iteration. Not only did he popularise the Tōkaidō, but he demonstrated its immense depth and visual potential in print.

Hiroshige’s contemporaries also made variations on the 53 Stations. Perhaps the most unusual is the Myōkaikō Gojusantsugi [The Cat Lover’s 53 Stations] by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861); an ukiyo-e triptych featuring over 55 cats, each representing a station on the Tōkaidō. With its pale pink background, it is extremely charming and curious. The cats are also far more layered than they may initially seem; for the Nihonbashi station a cat is shown eating two sticks of dried bonito fish, which is an ingenious play on words – dried bonito is used in dashi (stock), and so by playing with two, pluralised to nihon, the cat is depicted with nihon-dashi, ‘two sticks for dashi’, a pun on ‘Nihon-bashi’. Each cat follows a similar wordplay and demonstrates how the Tōkaidō can be interpreted in more playful ways.