A memorable synopsis of the Boston Tea Party can be read here: “The tea destroyers hailed from all walks of life. Men with strong backs and hard Yankee accents, they were a mix of young merchants, craftsmen, apprentices, and workers. They believed in a wrathful God, and they feared that the temptations of tea would turn them into tools of a corrupt, tyrannical empire. The grown men among them believed they were embarked on a noble deed of patriotic virtue. The younger boys thrilled to the idea of an evening spent wreaking chaos and destruction ... On the evening of December 16, they spoke for all the dissidents in Boston who had squared off against the policies of the British government. The Boston Tea Party wasn't a rebellion, or even a protest against the king - but it set in motion a series of events that led to open revolt against the British Crown” (Carp).

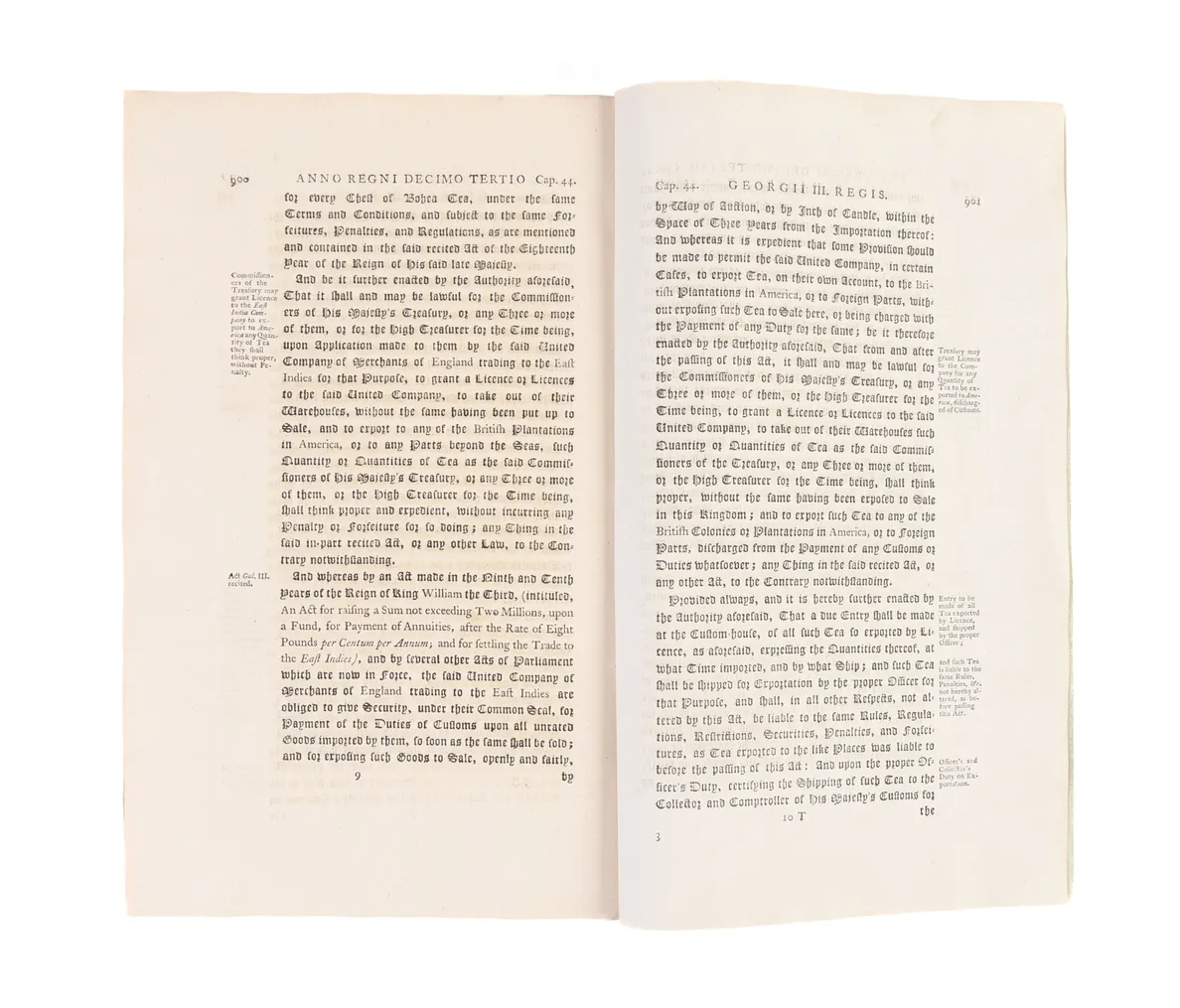

Great Britain clearly hadn’t foreseen the ramifications of what appeared to be a straightforward piece of legislation. The Tea Act was passed by the British Parliament on April 27th 1773 and received Royal assent shortly after on the 10th May. The Act allowed the faltering East India Company to export tea directly to America without paying customs duties. This gave the East India Company an effective monopoly on the lucrative trade by ensuring that it could be sold cheaply enough to undercut even the tea smuggled into the colony. The Act was passed in Britain, “without opposition, nay, almost without remark” (Mahon) with Benjamin Woods Labaree noting that “Perhaps no bill of such momentous consequences has ever received less attention upon passage in Parliament”.

Not everyone was so complacent. Benjamin Franklin writing in London to Thomas Cushing on 4th June 1773 stated: “It was thought at the beginning of the session, that the American duty on tea would be taken off. But now the wise scheme is, to take off so much duty here, as will make tea cheaper in America than foreigners can supply us, and to confine the duty there, to keep up the exercise of the right. They have no idea that any people can act from any other principal but that of interest; and they believe, that three pence in a pound of tea, of which one does not perhaps drink ten pounds in a year, sufficient to overcome all the patriotism of an American.”

Indeed, in America that Act was seen as another aggressive piece of tyrannical taxation and recalled previous protests such as those surrounding the Stamp Act of 1765. Instead of celebrating the lower price, Americans were furious that their own middlemen in the tea trade were being driven out of business. This culminated in the so-called Boston Tea Party on 16th December 1773 when colonists (many dressed as Native Americans) boarded East India Company ships in Boston harbour and dumped the tea (valued at £18,000 - nearly a million dollars’ worth today) overboard. A revolution ensued and America was born.

Parliamentary Acts were issued individually – as here – with a separate title-page and as continuous runs (hence the pagination). A group of individual acts including the present act (as the leading item) were sold at Sotheby’s in 1988 for $3,850. A copy of the (more common) Stamp Act of 1765 (An Act for Granting and Applying certain Stamp Duties…in America) sold at Sotheby’s in April 2010 ($7,000). A copy of the Stamp Act is for sale online priced at $27,500.

Rare. ESTC records copies at Lincoln’s Inn; Newberry, Tulane University, Library of Congress, University of Minnesota and Yale. OCLC adds a copy at the American Philosophical Society Library. Not in Church, not in Howes, not in Sabin. Carp, B., Defiance of the Patriots: the Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (Yale, 2010); Mahon, History of England (1858), vol V, p.319; Woods Larrabee, B., The Boston Tea Party (1979), p.73.