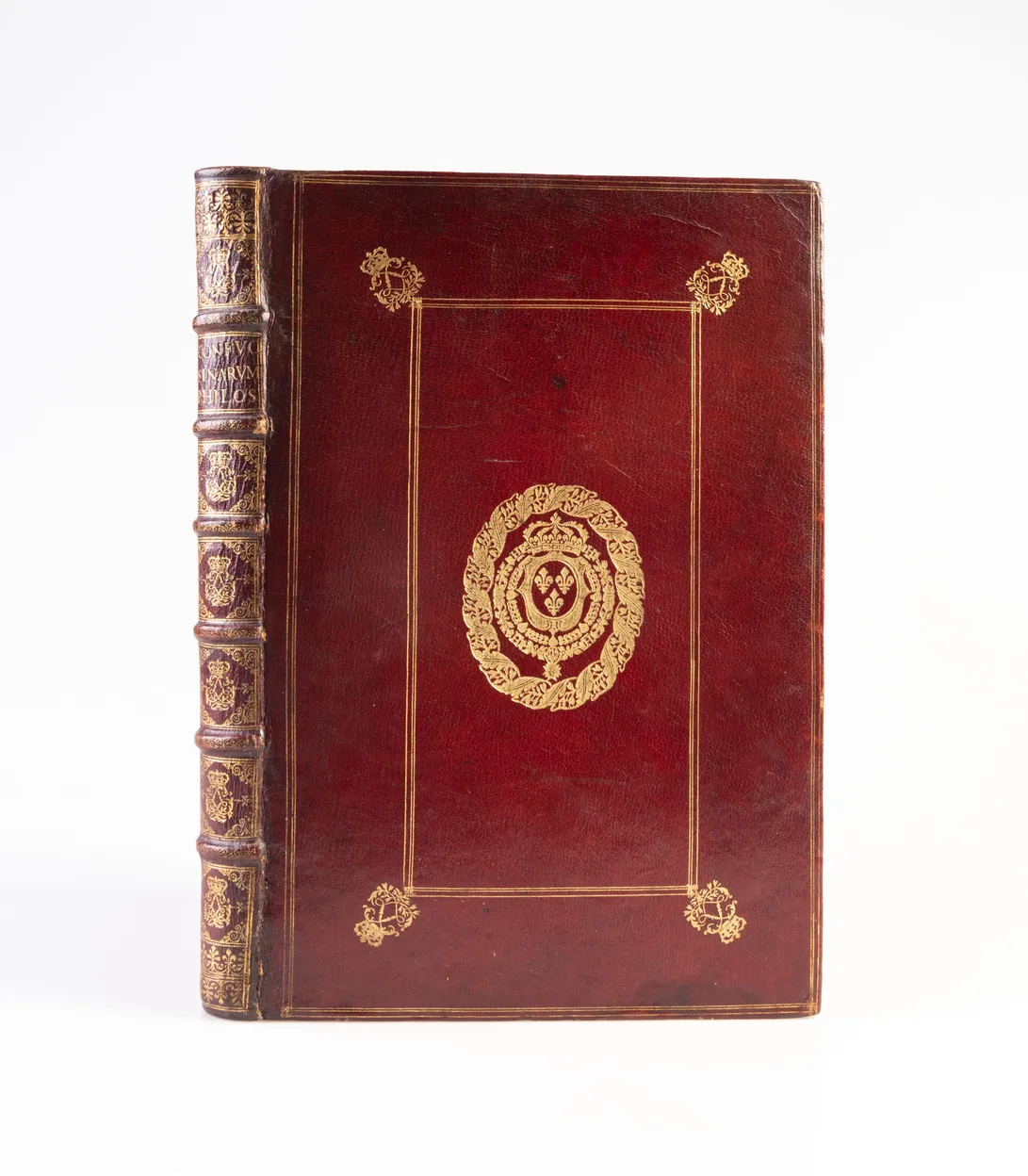

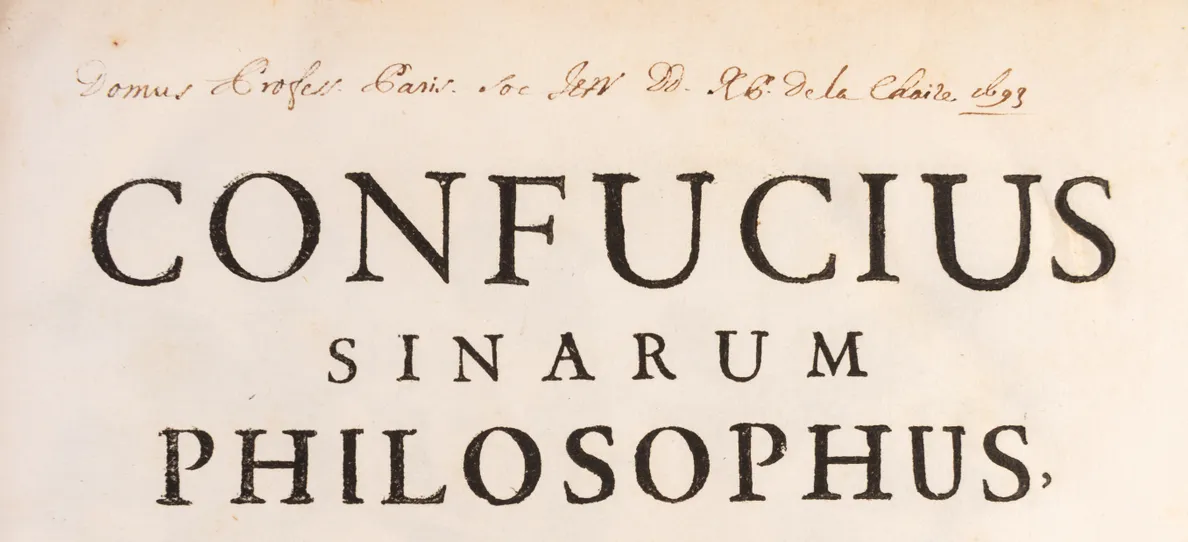

A Royal Presentation copy from Louis XIV (The Sun King, 1643-1715) to his confessor Francois de la Chaise (1624-1709). The Professed House mentioned on the title-inscription was the official residence for the confessors to the Kings of France. It was located on the Rue St. Antoine in Paris.

The present work is considered the first comprehensive discussion of Confucian thought, as well as a landmark in the transmission of Chinese culture throughout Europe. Much of the translation of the three Confucian Classics (Daxue, Zhongyong, Lunyu) was undertaken by the three Jesuits mentioned in the title, Prospero Intorcetta (1625-1696), Christian Wolfgang Herdtrich (1625-1684), and François de Rougemont (1624-1676). The book of Mencius would have considerably increased the size and cost of the publication and p. 159 states that they are hoping to supply a translation of that important work at a later date.

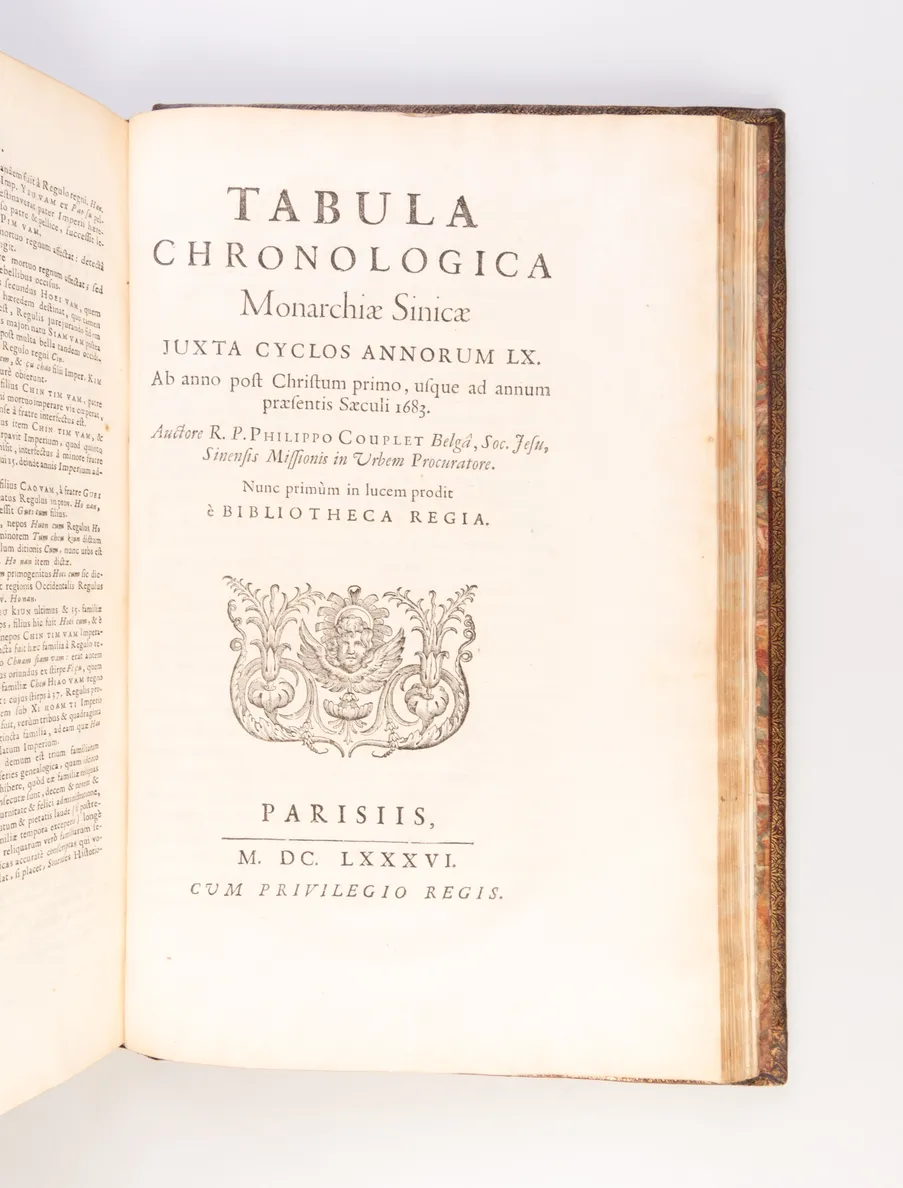

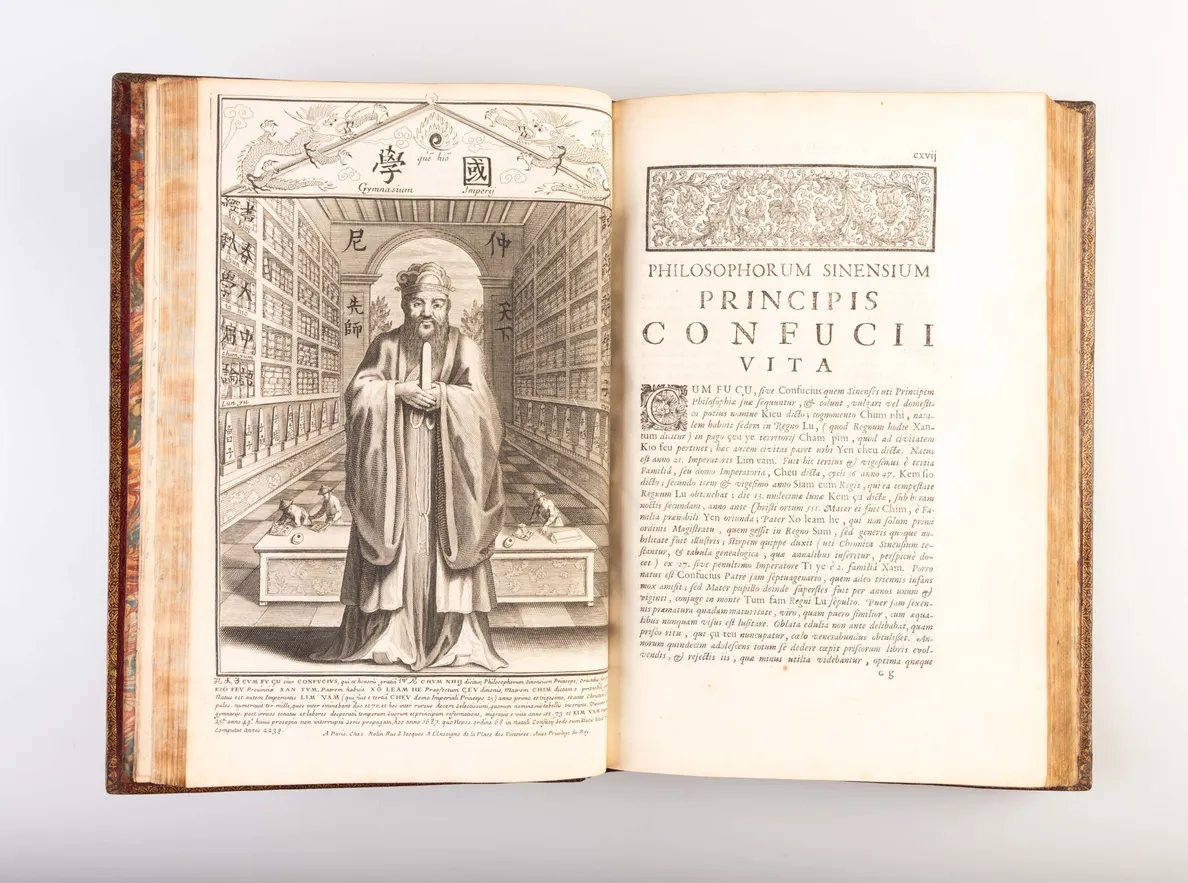

The author and editor Philippe Couplet (1623-1693), a Flemish Jesuit, made a number of important contributions to the book: The long introduction includes an explanation of the 64 Yijing hexagrams, as well as a biography of Confucius. He was also responsible for the second part of the work consisting of the Tabula Chronologica ante Christum for the first three dynasties starting with the legendary Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), followed by a genealogical table of the three families and 86 successors of Huangdi starting from the year 2697 BC. Seemingly innocuous, this chronology caused a storm amongst theologians in Europe because it threw into question the accuracy of western biblical chronology, by clearly demonstrating that world history was older than the Bible allowed for. The second Tabula Chronologica Monarchiae Sinicae post Christum records the succession of Dynasties and Emperors together with major events up to 1683. It is the first summary of Chinese history to be published in Europe. The final three text-leaves provide interesting statistical information about the 15 provinces. The work also includes an engraved map with the locations of the Jesuit missions throughout the empire. A full-page engraved portrait shows Confucius in front of a library containing his own works as well as the writings and the ancestral tablets of his followers. The characters on the back wall read: "Confucius, the foremost teacher under heaven". Couplet could hardly have been more complementary when he states in his preface: "One might say that the moral system of this philosopher [Confucius] is infinitely sublime, but that it is at the same time simple, sensible, and drawn from the purest sources of natural reason... Never has Reason, deprived of Divine Revelation, appeared so well developed nor with so much power." (Arnold H. Rowbotham. The Impact of Confucianism on Seventeenth Century Europe". in: The Far Eastern Quarterly Vol. 4, No. 3 (May, 1945), pp. 224ff.).

Louis XIV had a strong interest in China, which in no small measure goes back to his meeting with Couplet in Versailles on September 15th, 1684, accompanied by the Chinese convert Michael Shen (see also item 5). Couplet had recently returned from China for a tour of European capitals in order to raise funds for the Jesuit mission and to persuade Jesuits with good knowledge of astronomy and mathematics to come to China, and the audience with the Sun King had in fact been arranged by no other than the confessor Francois de la Chaise himself. It was a huge success: The king took great pleasure in being instructed by Shen in the use of chopsticks, he has him recite prayers in Chinese, and had the fountains in the gardens switched on, a privilege usually reserved for ambassadors and the highest guests. Couplet carried the manuscript of the Confucius Sinarum Philosophus in his luggage and the King not only offered to finance the publication in an expensive folio, but also wholeheartedly supported the plan of sending French Jesuits to the Kangxi Court. Part of his motivation was no doubt to challenge the Portuguese Padroado, which gave the Portuguese Kings the right to control missionary activity in India and the Far East. In 1685 six French Jesuits (Tachard, Fontaney, Bouvet, Gerbillon, Le Comte & Visdelou) were sent to China, which not only enlarged French influence in Peking, it also ensured French dominance in cultural exchange with China until the end of the 18th century.

Even more astonishing is the effect the work had on philosophers in the West: French Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau and Leibniz in Germany praised many aspects of Confucian theory: His insistence on self-cultivation, harmony, and righteousness, and the correlation between virtue and successful government inspired new social theories and were seen to have parallels in natural reason. The Confucian concept of meritocracy (for example recruiting government officials through public examinations) was suddenly seen it as a viable alternative to the traditional Ancien Régime of Europe. Voltaire claimed that the Chinese had "perfected moral science" and advocated nothing less than an economic and political system after the Chinese model.

Couplet and Shen were detained in Lisbon for three years. The Portuguese authorities clearly took offence for not having respected the procedures relating to the Padroado. Unfortunately, they both died on separate return voyages to China.

Cordier 1392-1393; Lust 724; Morrison 438-439; Pei-tang 1358; Pfister 326-327.

Philippe Couplet, S.J. (1623-1693): The man who brought China to Europe. Louvain, 1990.