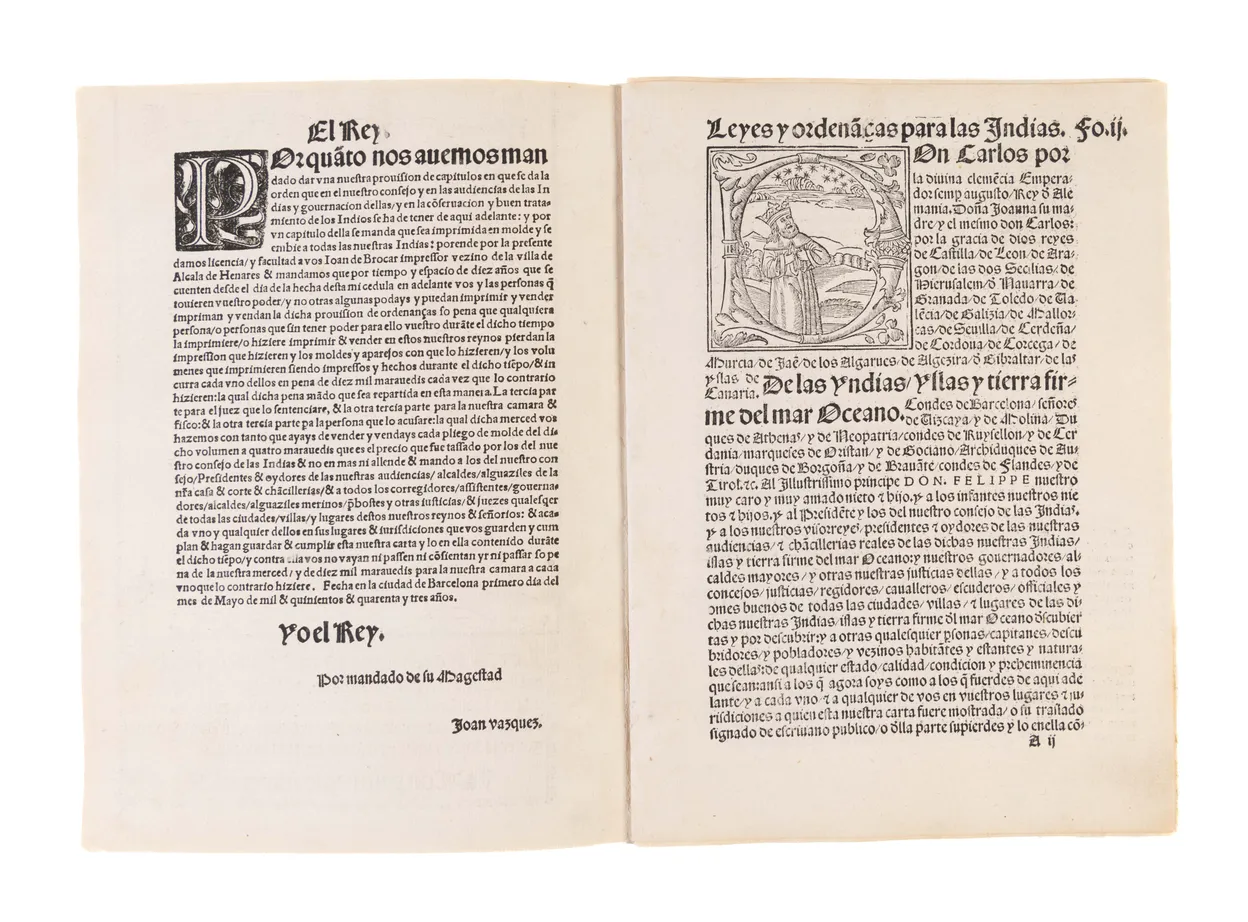

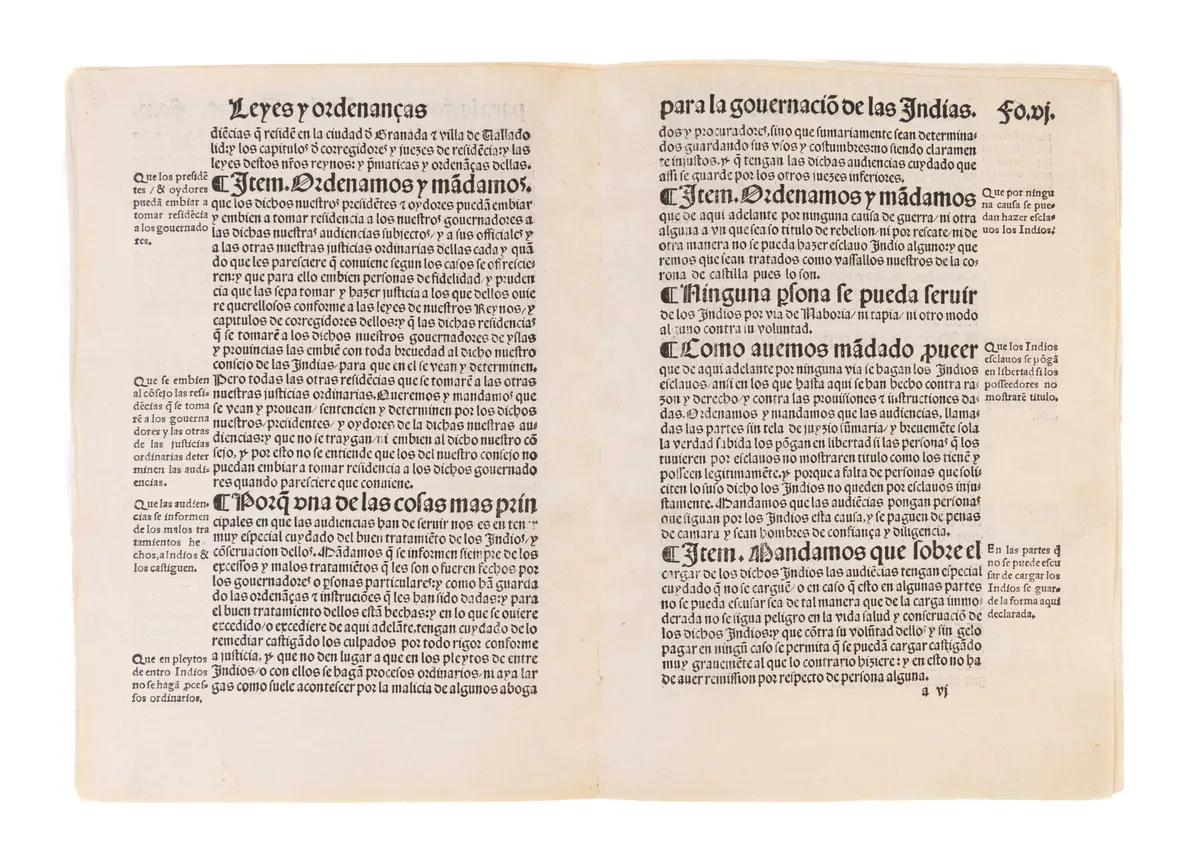

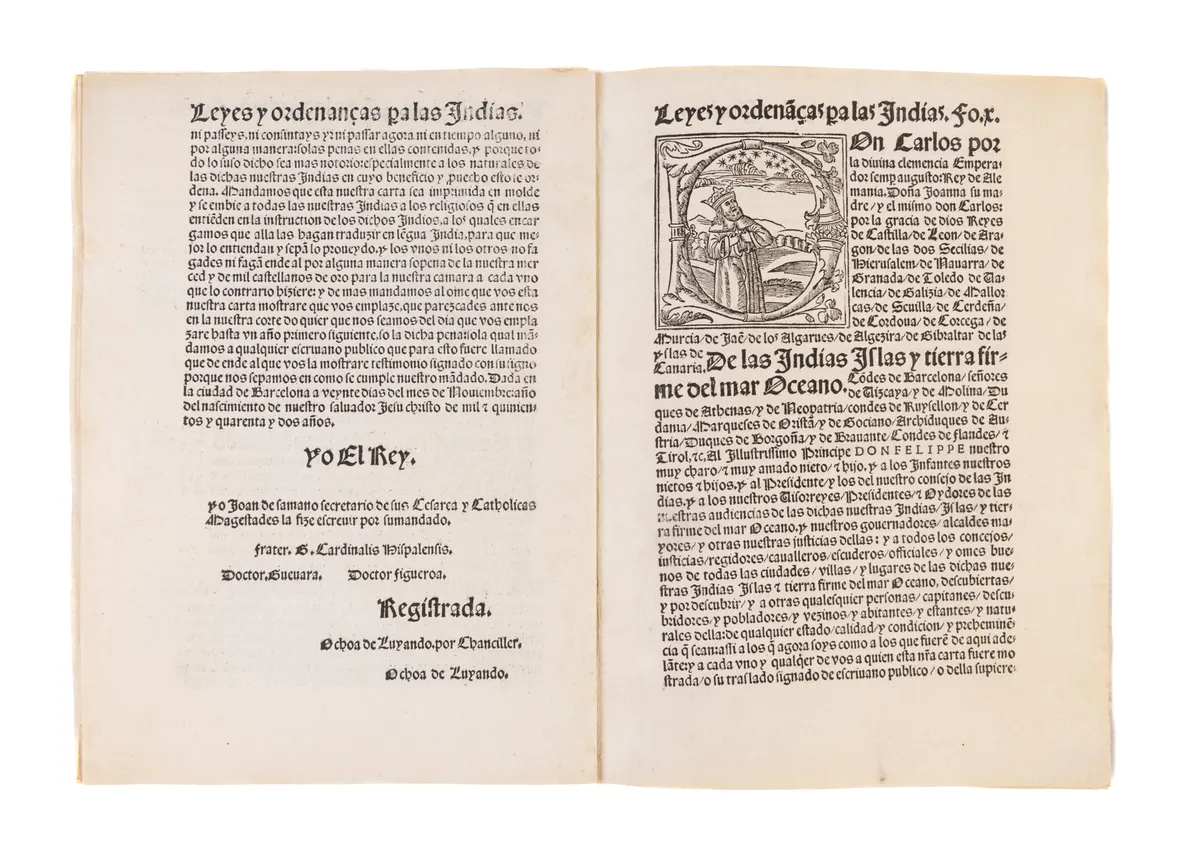

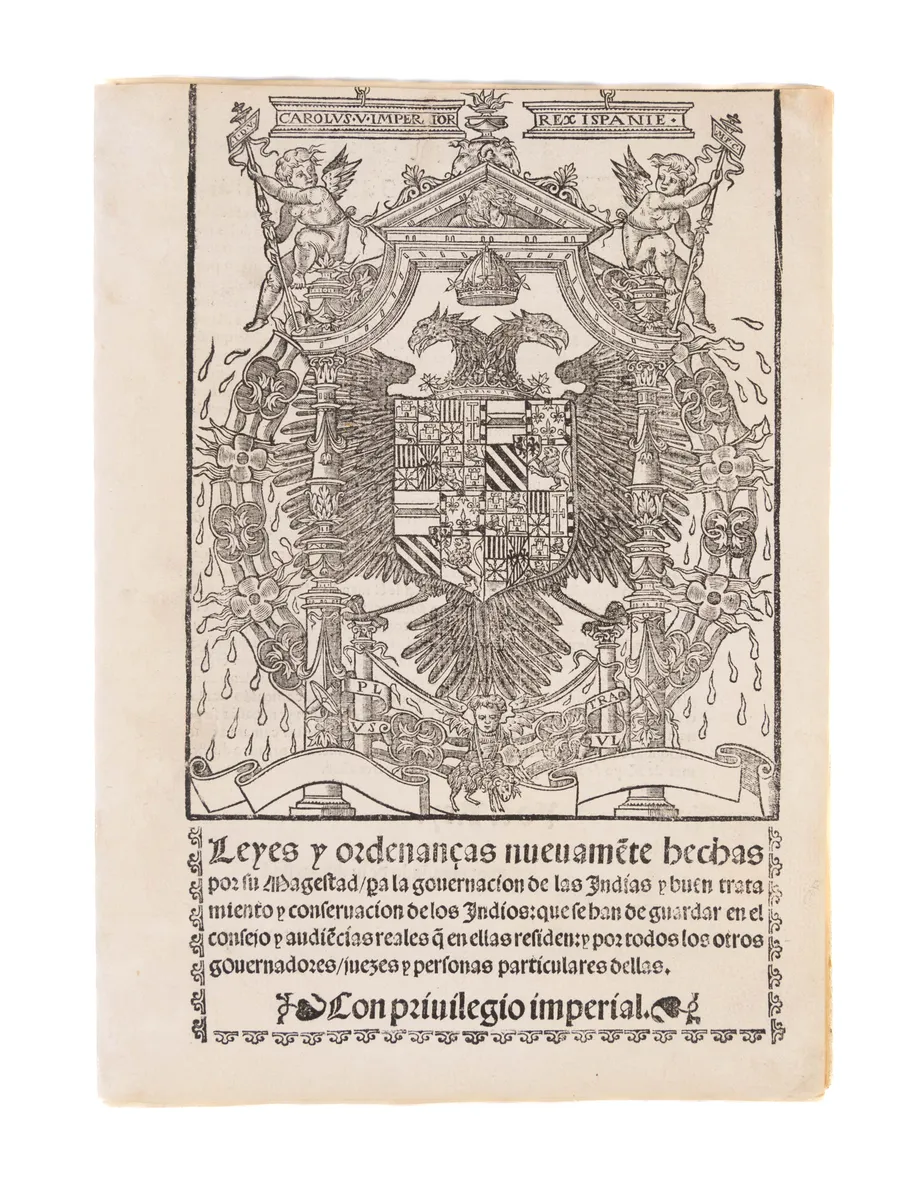

Exceedingly rare and important: the first book of American law. Published just fifty years after Columbus first landed on American soil, the Leyes, or New Laws as they're also known, set out new regulations to provide better treatment for Indigenous Americans. Extraordinarily, it includes an abolition clause.

Hernán Cortes led the conquest of Mexico in 1519 and served as governor of New Spain from 1521-4. The impact of Spanish colonisation on the Indigenous population is well-documented, and while Cortes remains the poster-child for these excesses, the devastation commenced at first contact. "It took a full half century, from 1493 to 1543, to achieve, in legal and papal form, the complete cycle of devastation and degradation of the Aboriginal races ..." (Stevens & Lucas, ix). Of course, there was opposition, and this legislation was partly due to the efforts of Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), the Dominican Friar and "protector of the Indians" who wrote a series of works arguing for the better treatment of Indigenous Americans. In fact, Church notes that Las Casas "was actively interested in them and aided much in their promulgation". These New Laws were for the territory including New Spain, Peru, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Hispanola.

This document seeks to establish a number of precepts. First and foremost it sets out to codify better treatment for the Indigenous people [all translations are from Stevens]: "because our chief intention and will has always been and is the preservation and increase of the Indians, and that they be instructed and taught in the matters of our holy Catholic faith, and be well treated as free persons."

The Crown takes a further step in this direction with the following: "We ordain and command that from henceforward for no cause of war nor any other whatsoever, though it be under title of rebellion, nor by ransom nor in other manner can an Indian be made a slave, and we will that they be treated as our vassals of the Crown of Castile since such they are."

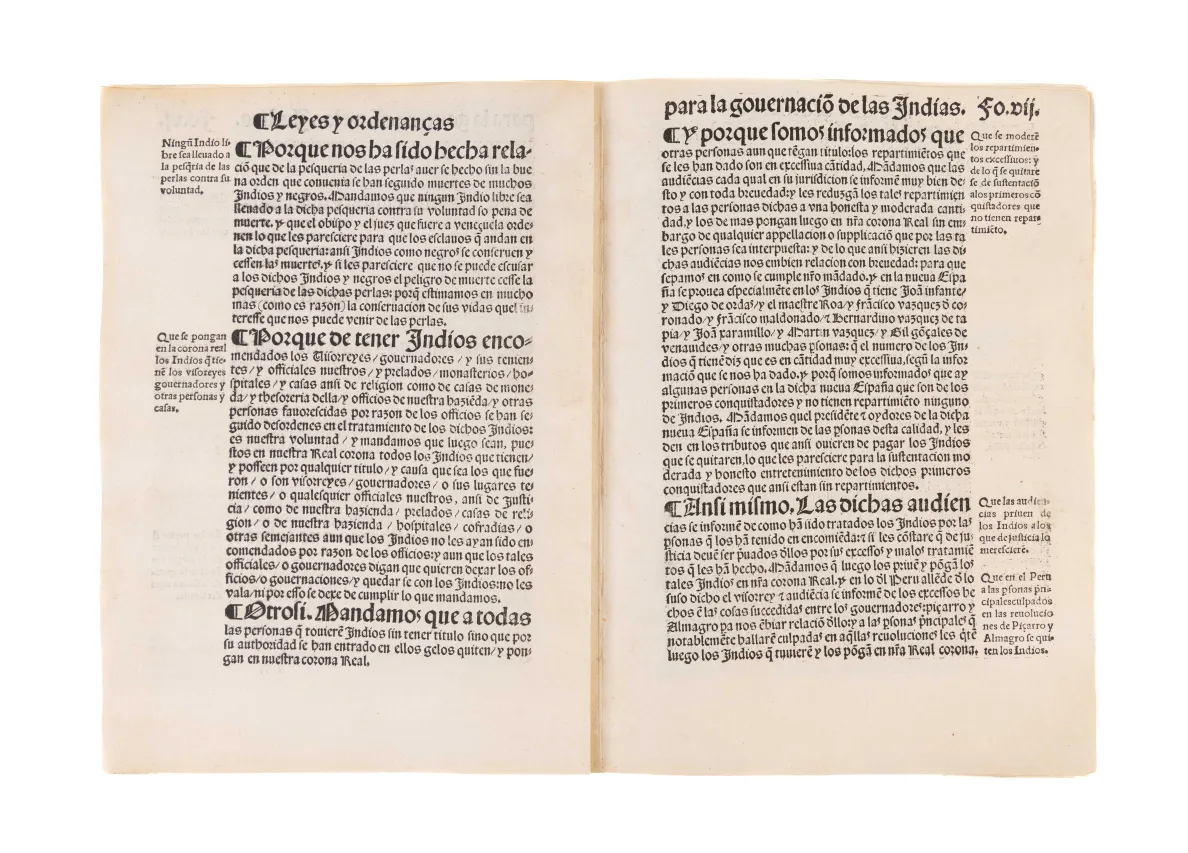

This anti-slavery law includes "those who until now have been enslaved against all reason and right and contrary to the provisions and instructions thereupon." Furthermore, "no risk of life, health and preservation of the said Indians may ensue from immoderate burthen; and that against their own will and without being paid, in no case be it permitted that they be laden, punishing very severely him who shall act contrary to this." This included working in the pearl fisheries. Critically, it states that any Indigenous Americans who are found being treated or held in such a manner will be removed and "placed under our Royal Crown."

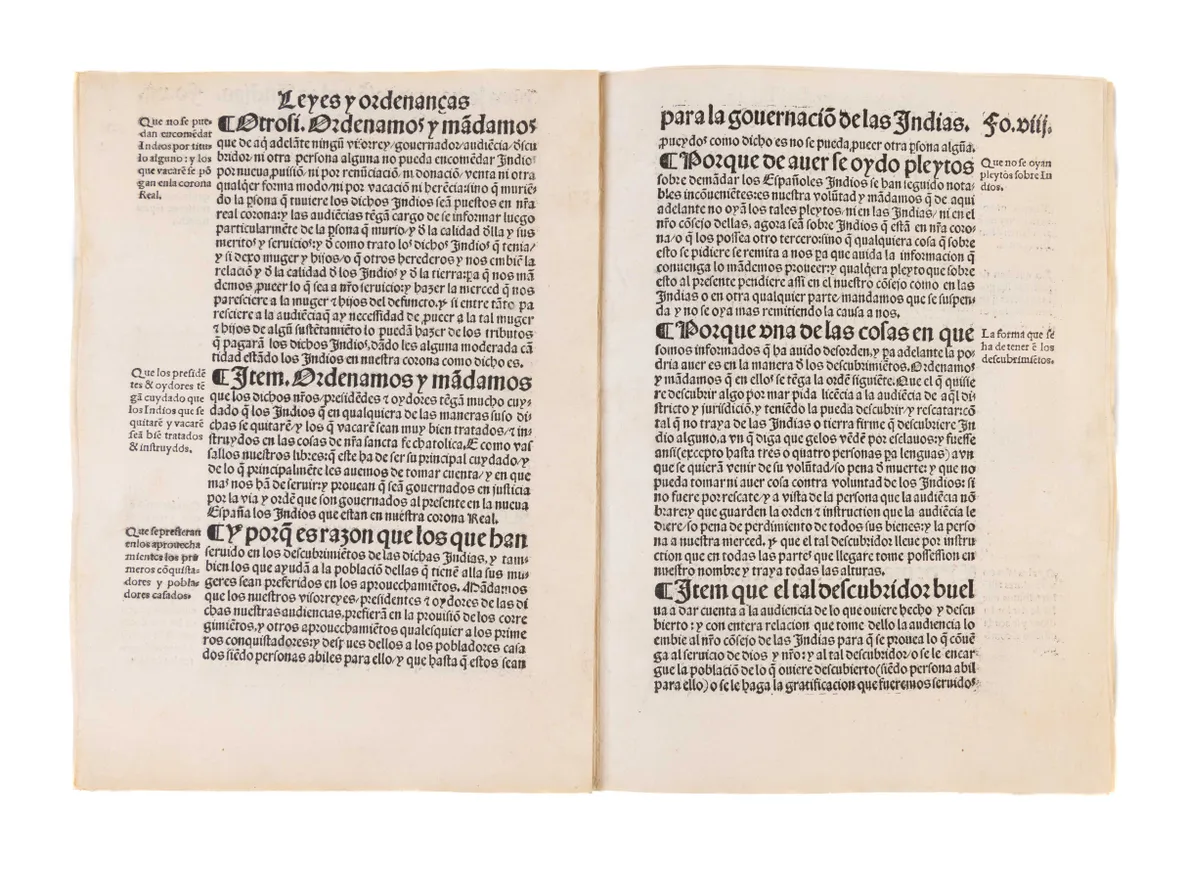

This leads us to labour practices in the Spanish Empire and the relationship between the Crown and colonists. "When the Spaniards conquered the New World, they resorted to a system of forced labor called the encomienda. An encomienda was an organization in which a Spaniard received a restricted set of property rights over Indian labor from the Crown whereby the Spaniard (an encomendero) could extract tribute (payment of a portion of output) from the Indians in the form of goods, metals, money, or direct labor services" (Yeager). In exchange, the encomendero, was obliged to provide for their protection, education, and religious welfare.

There are differences which distinguish this system from the slavery practised later in the Caribbean and United States. The Indigenous Americans were not owned, and thus could not be bought or sold; there was no inheritance built into the system (rights reverted to the Crown); nor could they be moved or relocated from their homes. But in practical terms - specifically the experience of the Indigenous American - there was little difference, and indeed many were enslaved outside of the encomienda system, which these New Laws addressed. To give an example of the scale of the system, Córtes himself was granted an encomienda that included 115,000 people and "it was generally recognized that some of these personal service activities contributed greatly to the destruction of the Indians" (Batchelder and Sanchez, 49).

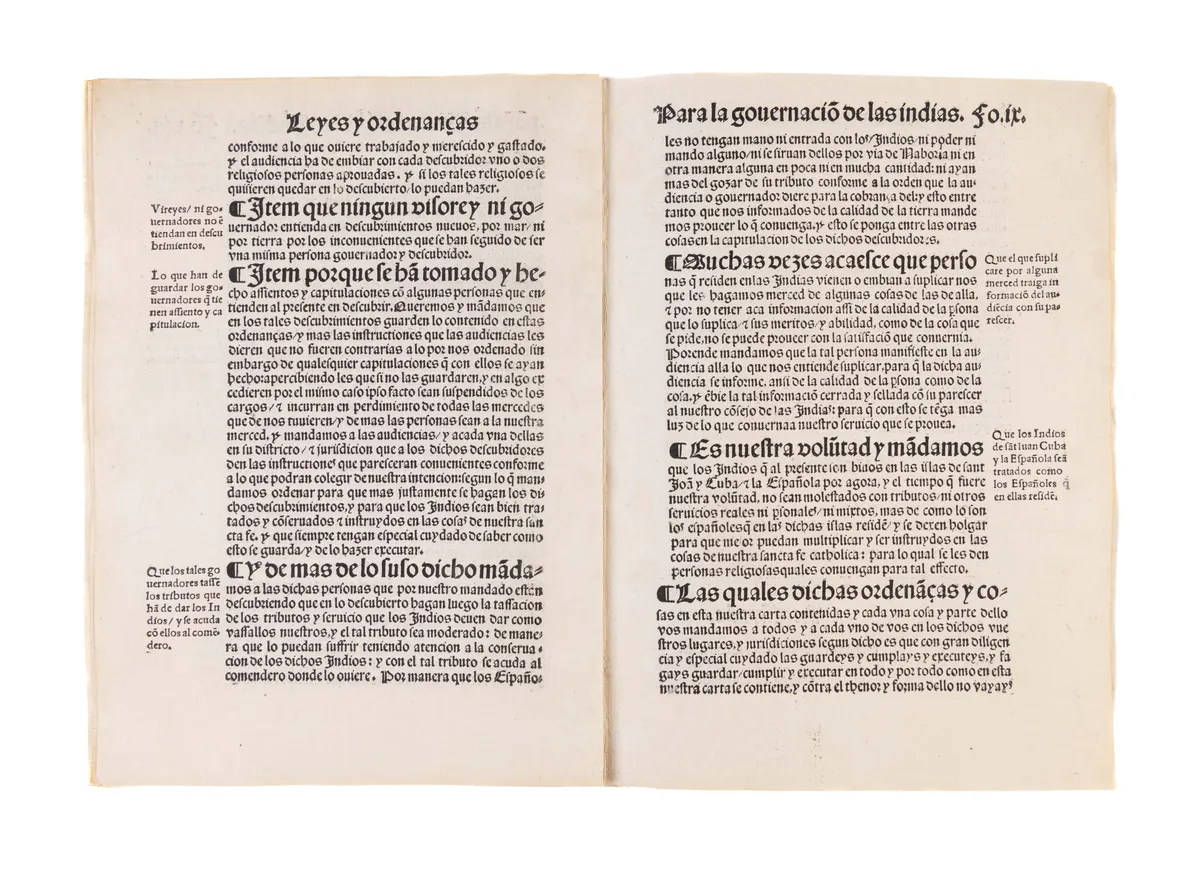

Here the New Laws set out the following: "These regulations limited personal services to encomenderos, made Crown officials responsible for determining the amount and composition of the tribute from encomiendas, prohibited the creation of new encomiendas and the reassignment of old ones and freed Indian slaves" (ibid, 57). If it seems too good to be true, it was. The Crown applied these restrictions largely to curtail the power (and wealth) of their own colonists. Importantly, with rights reverting to the Crown, which could also be confiscated, Spain retained complete control over its American colonies. And in what became a truism for colonies in the Americas for the next four hundred years, the implementation of these laws was hindered by lobbying by colonists.

Harisse confirms this: “They were issued especially for the better treatment of the Indians, and, we believe, for limiting the partitions of lands among the conquerors. Leon Pinelo states, on the authority of Juan de Grivalja, that these laws 'tan odiosas,' were prompted by the publication of the manuscript tract 'Dies i seis remedios contra la peste que destruye las Indias.' They were issued at Barcelona, November 20th, 1542, completed at Valladolid, July 4th, 1543, and ordered to be printed, and enforced immediately throughout the Indies."

The New Laws concerns would reverberate through the next four hundred years of colonization, both its riches and horrors.

There are a handful of copies in institutions: JCB, Huntington, Newberry, Indiana, NYPL, Michigan Law, NLS, BL, and BNE. We find just two recorded copies for sale - Quaritch in 1889 (£40) and Lathrop Harper in 1941 (USD$2950). Another listed at Sotheby's in 1962 was withdrawn.

The copy at the BL is on vellum. We've compared ours to the one held at the Newberry Library and it's the same.

Brunet “Manuel du Libraire,” III., col. 1042; Church, 80; Harrisse, “Bib. Am. Vet.,” No. 247; Sabin, 40902; Batchelder, R.W. & Sanchez, N., "The encomienda and the optimizing imperialist: an interpretation of Spanish imperialism in the Americas" in Public Choice, Vol. 156, No. 1/2 (July, 2013) pp.45-60; Stevens H., & Lucas, F., Leyes y ordenanças nuevamente hechas: the new laws of the Indies for the good treatment and preservation of the Indians ... (London, 1893); Yeager, T., "Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown's Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America" in The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Dec., 1995), p.843.