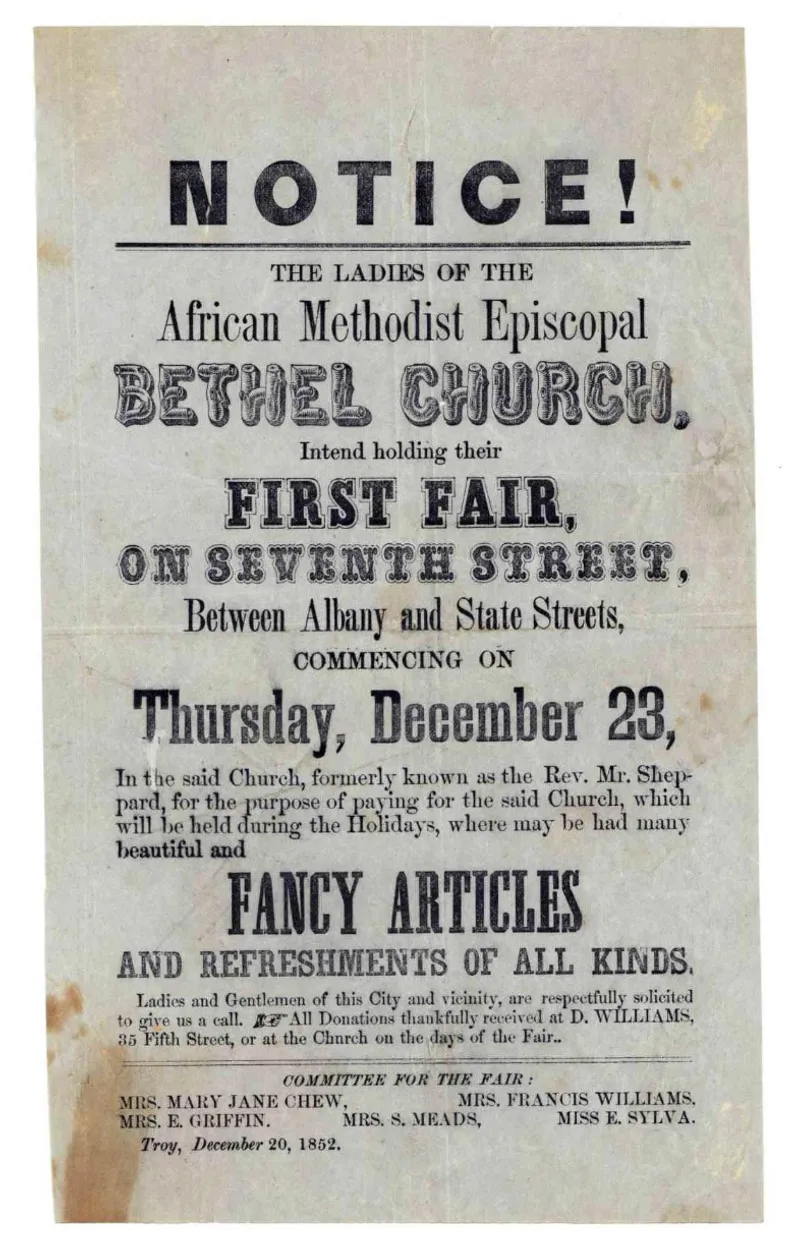

An extremely rare survival: a broadside advertisement for an antebellum fair held by an African American church.

The first documented Ladies Fair was held in Baltimore in March, 1827, in aid of civilians in the Greek War of Independence. They became important events for religious, social, and political causes and were opportunities for women to volunteer. As the fair movement spread widely through groups of white Protestant women in the decades prior to the Civil War, it would likewise take root in Black communities by mid-century, often in the context of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

This 1852 handbill announces the first fair to be held by the ladies of the AME Bethel Church, the proceeds of which were to support the cost of "paying for the said church." Typically, the date was scheduled near the Christmas holidays and included the sale of refreshments and "Fancy Articles," which usually included needlework, embroidery, knitting, and crochet, as well as shell and waxwork.

Historian Jualynne E. Dodson (2002) clarified three ways that women accrued power within the structure of the AME church. First, women helped to spread African Methodism and drew large numbers of new members, women and men, into the fold. Next, the church established a wide array of groups for women, beginning as early as 1828 with Sarah Allen’s Daughters of the Conference. Finally, Dodson identifies "indispensable resources," material and non-material, that women brought to the church organization, including education, community leadership, labor, and finances. Their financial prowess was especially noteworthy and made a significant impression on Black men in leadership positions. All of these paths came together in the context of fundraising fairs, which as Jon Butler notes for New York City, were becoming “as ubiquitous among Black congregations as ... among white Catholics and Protestants” (2020:126).

Where most Christian denominations are formed along theological lines, in 1816, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was one of the few established specifically in response to the discrimination members suffered at home and while practising. The AME Church was established at Philadelphia in 1816, when sixteen Black delegates convened and elected Richard Allen as the denomination's first bishop. Allen was not only financially independent but in 1794 had already founded the Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia. Recognising the need for a wider conference, he joining together with five other African American congregations and created the first entirely independent Black denomination in the United States.

This first fair for the AME Bethel Church in Troy was held the same year that Harriet Beecher Stowe's landmark novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, was published and so sentiment would've been high in this congregation.

One of the members of the fair committee was Mrs. Mary Jane Chew, the wife of prominent Troy abolitionist and restaurant owner Daniel Boston Chew. The Chews were both born in the South and may have arrived in Troy as fugitives; Daniel had worked as a waiter at Troy House hotel, owned by another Black abolitionist, William Rich, known for hiring freedom seekers as waitstaff. We find no other record of an AME Bethel Church in Troy, so it's possible that its congregation folded into the AME Zion Church, where Daniel was named as a member in his 1892 obituary. Troy’s antebellum African American community featured such renowned abolitionists as Henry Highland Garnet, David Payne, and Peter Baltimore. In October 1847, the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church, pastored by Garnet, hosted Frederick Douglass and the National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends. Troy’s AME Zion Church was established in 1830, followed just three years later by its African Female Benevolent Society.

While OCLC lists several examples of broadsides for anti-slavery fairs held by white abolitionists, we locate only one comparable example issued by African American women, an 1847 handbill for a fair by the “ladies (of color)” of Frankfort (KY), held at the Clements Library.

Butler, J., God in Gotham: The Miracle of Religion in Modern Manhattan. (Harvard University Press, 2020), p.126; Dodson, J.E., Engendering Church: Women, Power, and the AME Church (Rowman and Littlefield, 2002).