A remarkable collection of twenty grave-stone rubbings that chart the successes and eventual decline of the Jesuits at the court in Peking.

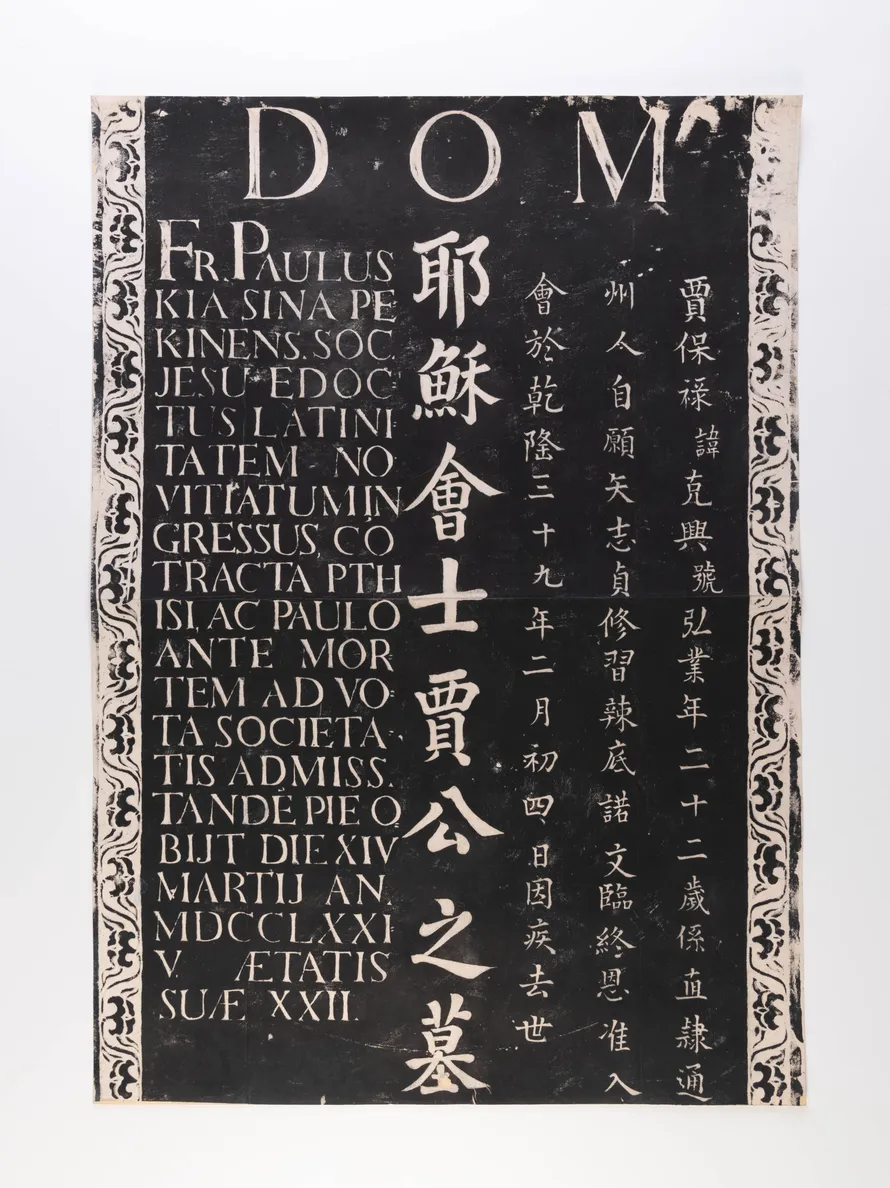

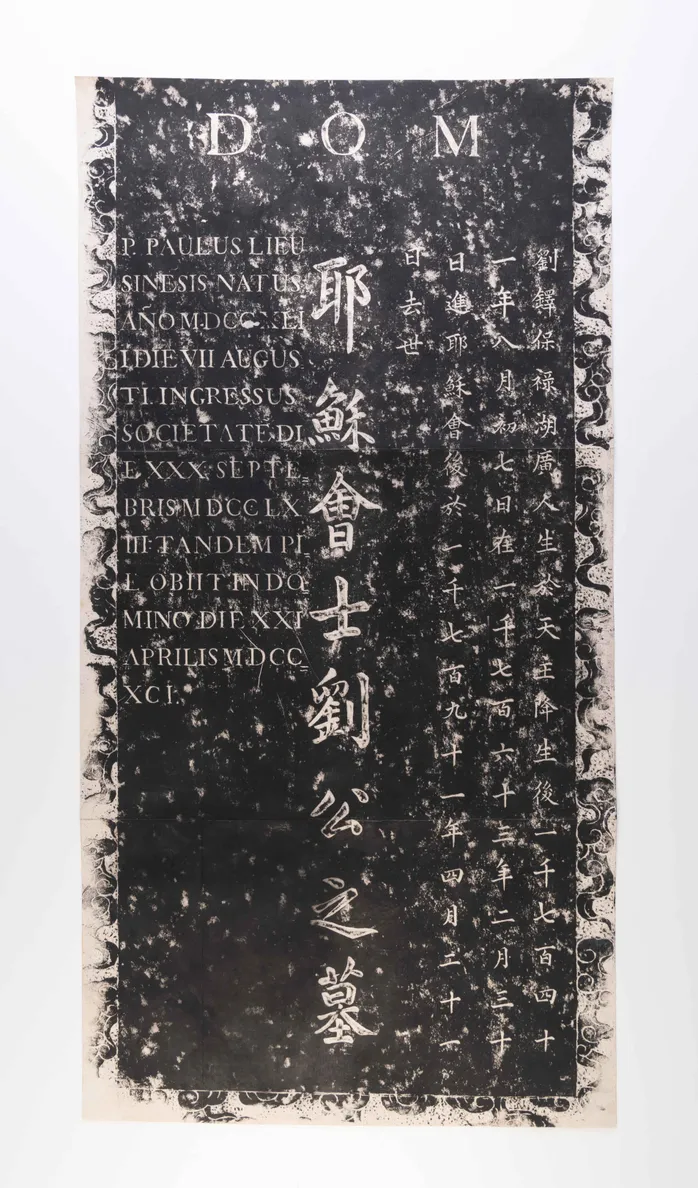

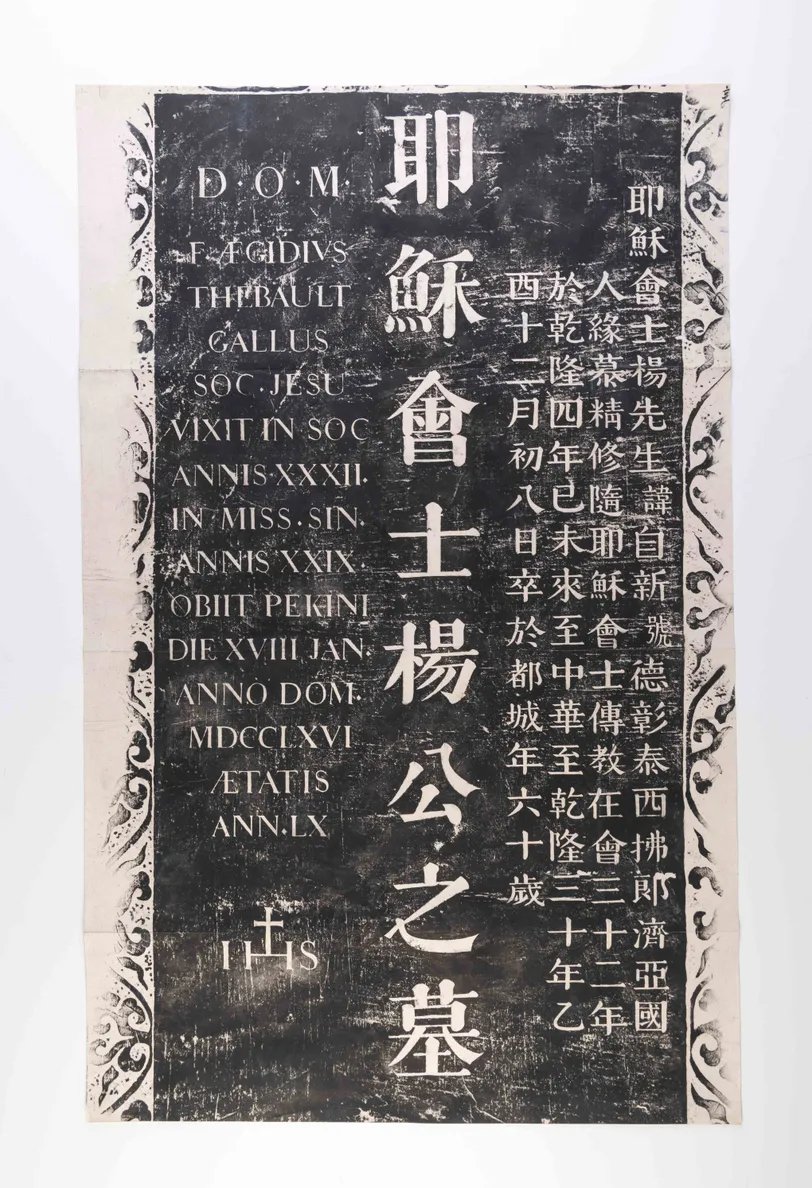

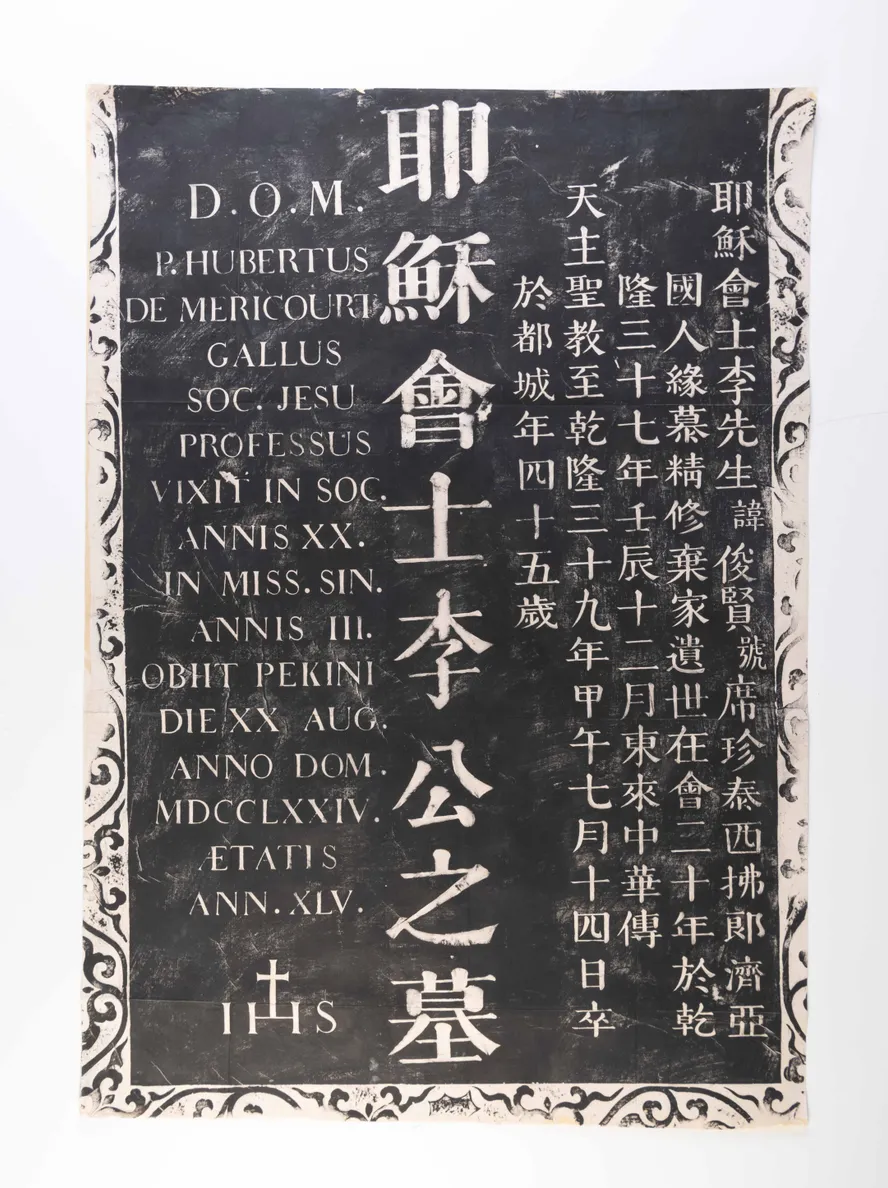

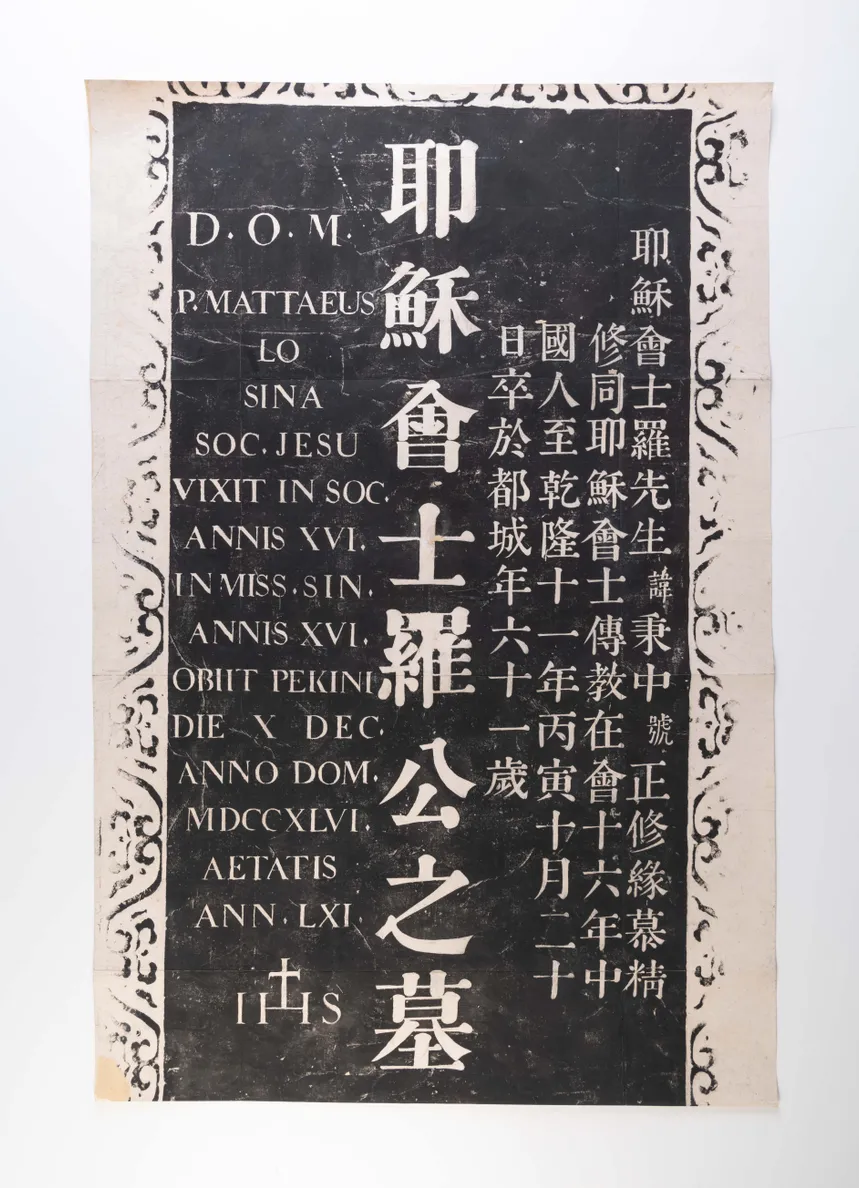

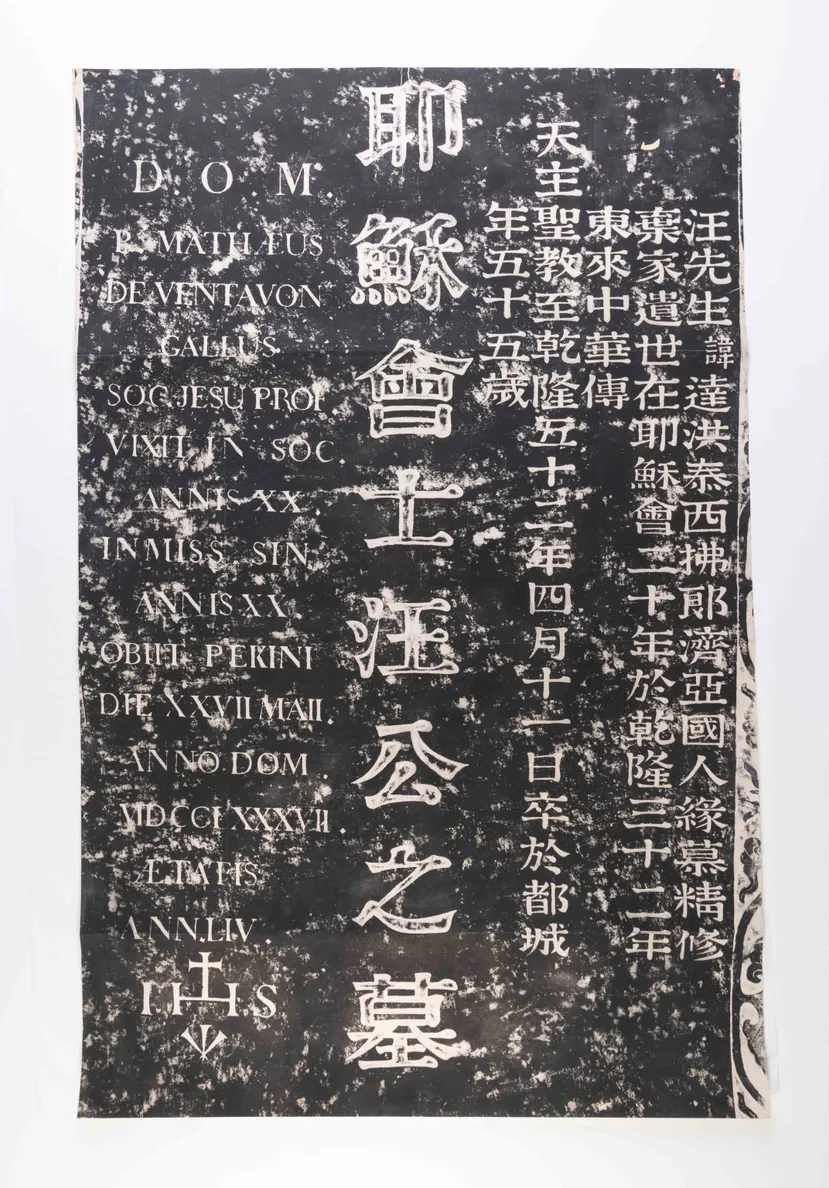

This group provides a fascinating overview of the range of characters, nationalities, and occupations that the Jesuits represented. Far from simply living the good life at the Imperial Court some of them dealt with immense challenges, threats, hardships and obviously none of them ever returned to their home countries. Notably, our rubbings include the tombs of four Chinese converts.

Unfortunately, we know far too little about the Chinese Jesuits’ personal backgrounds or how they were introduced to the Jesuit cause. There are a number of reasons why Western scholars have not paid enough attention to Chinese Jesuits. Much of their focus has tended to focus on the Western side, possibly due to the language constraints. Converts and their families may have been in danger after the Edict of Toleration was withdrawn in 1774, and some of their graves were destroyed during the Boxer Rebellion, adding to the difficulties.

The Field Museum in Chicago has a collection of over 4000 Chinese stone rubbings which had been collected by the German Sinologist Berthold Laufer (1874-1934). It is the largest collection of stone rubbings in a public institution outside of China. Amongst them is a group of 89 rubbings of Jesuit gravestones (see: Walravens (ed.): ‘Catalogue of Chinese Rubbings from Field Museum’ 1981). Within our collection of 20 rubbings, 12 of the gravestones are not represented in the Field Museum’s collection.

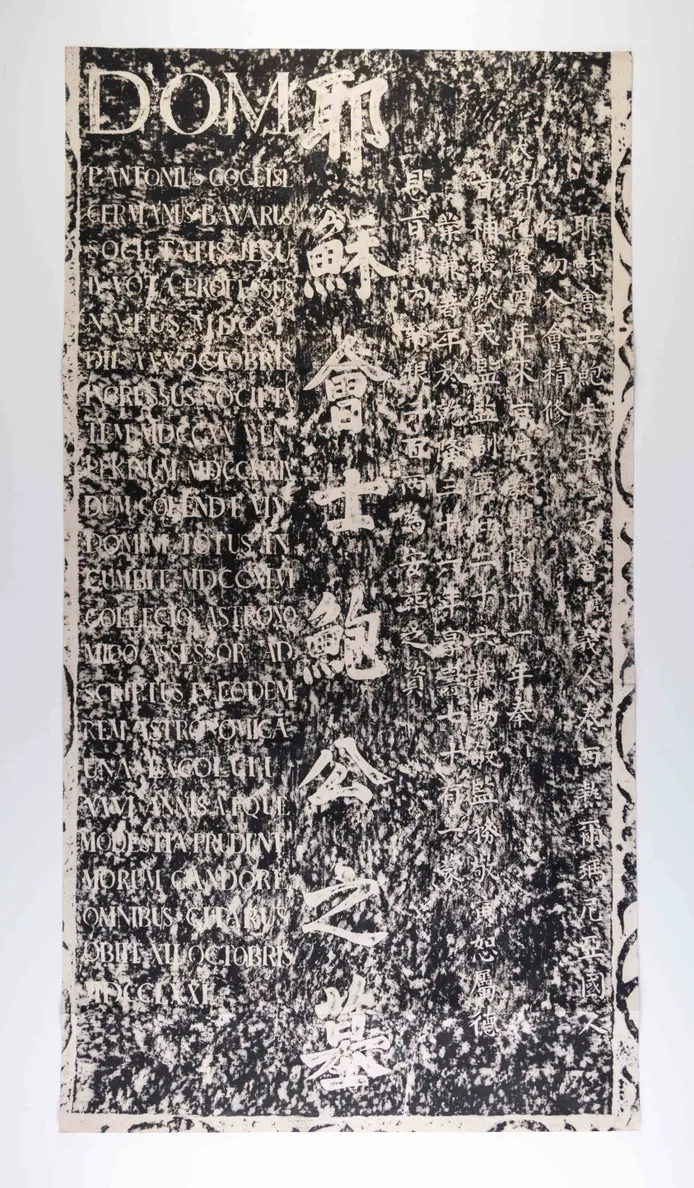

Between the opening of Peking in the 1860s (after the Second Opium War) to 1900 (Boxer Rebellion) there was a relatively brief window of opportunity when the present rubbings could have made; The Field Museum’s holdings were made after the Boxer Rebellion when the stones were already in visibly worse condition. The present collection therefore records a moment in their history before some of the graves were damaged or destroyed.

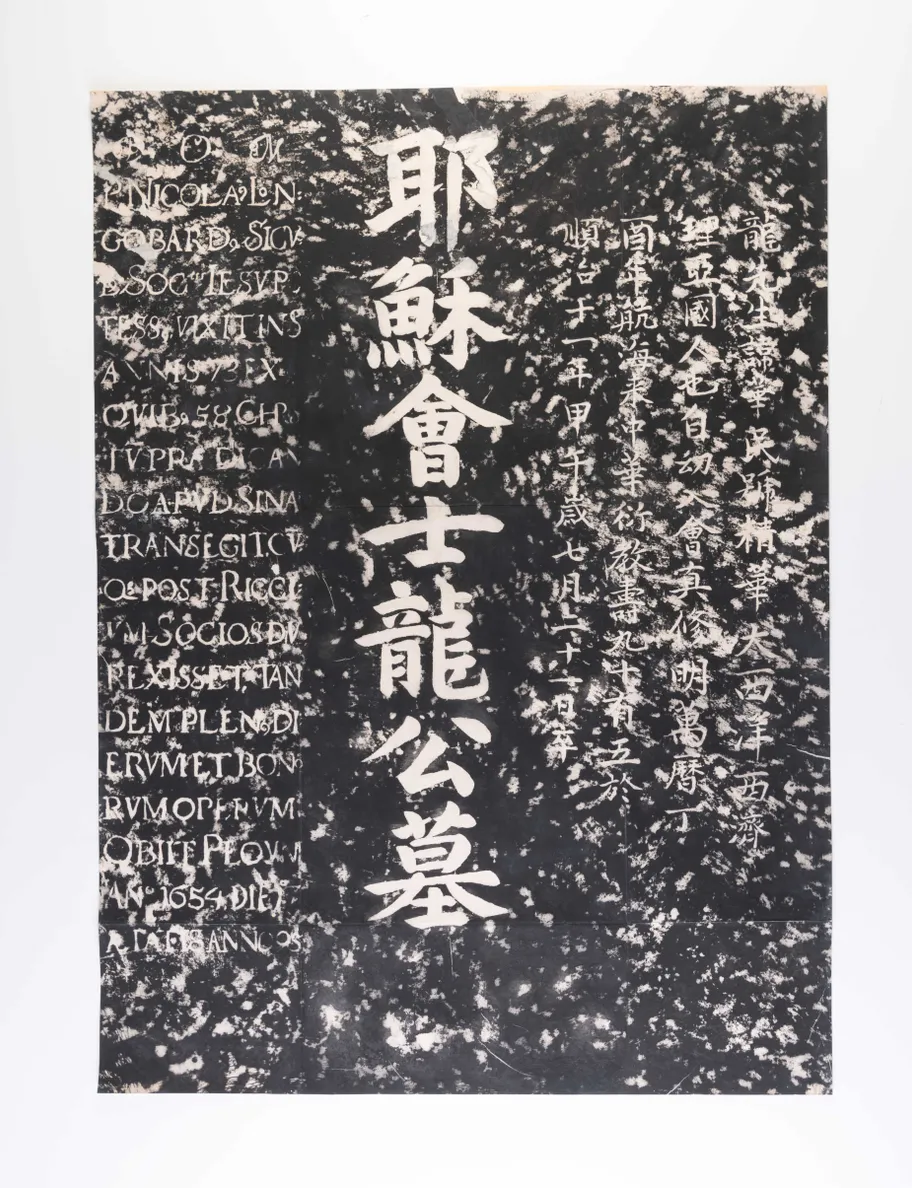

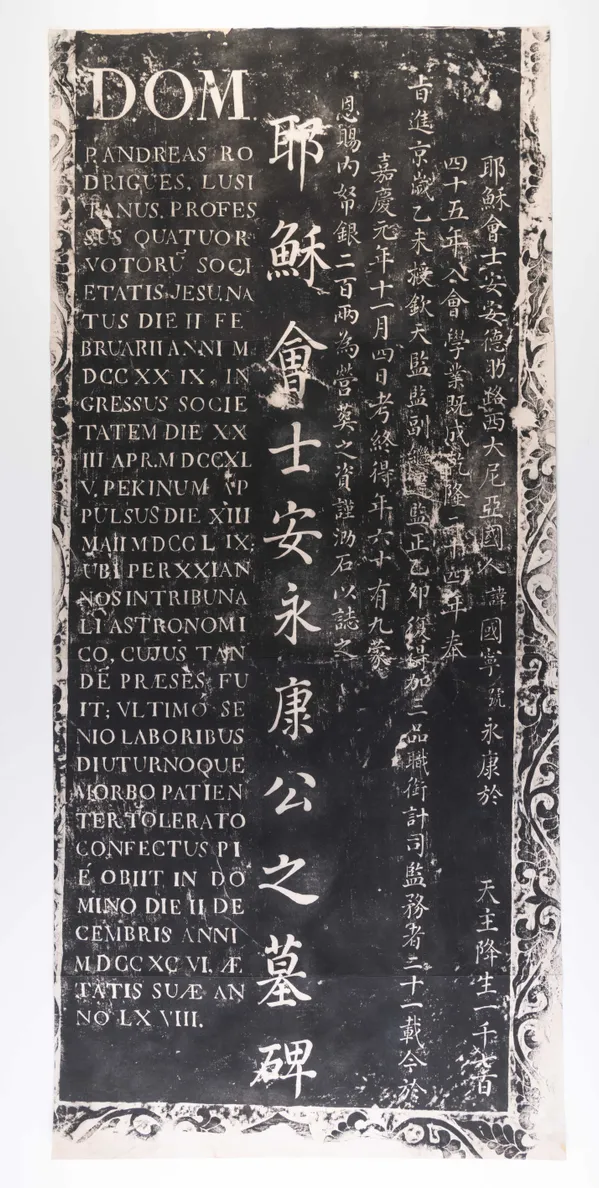

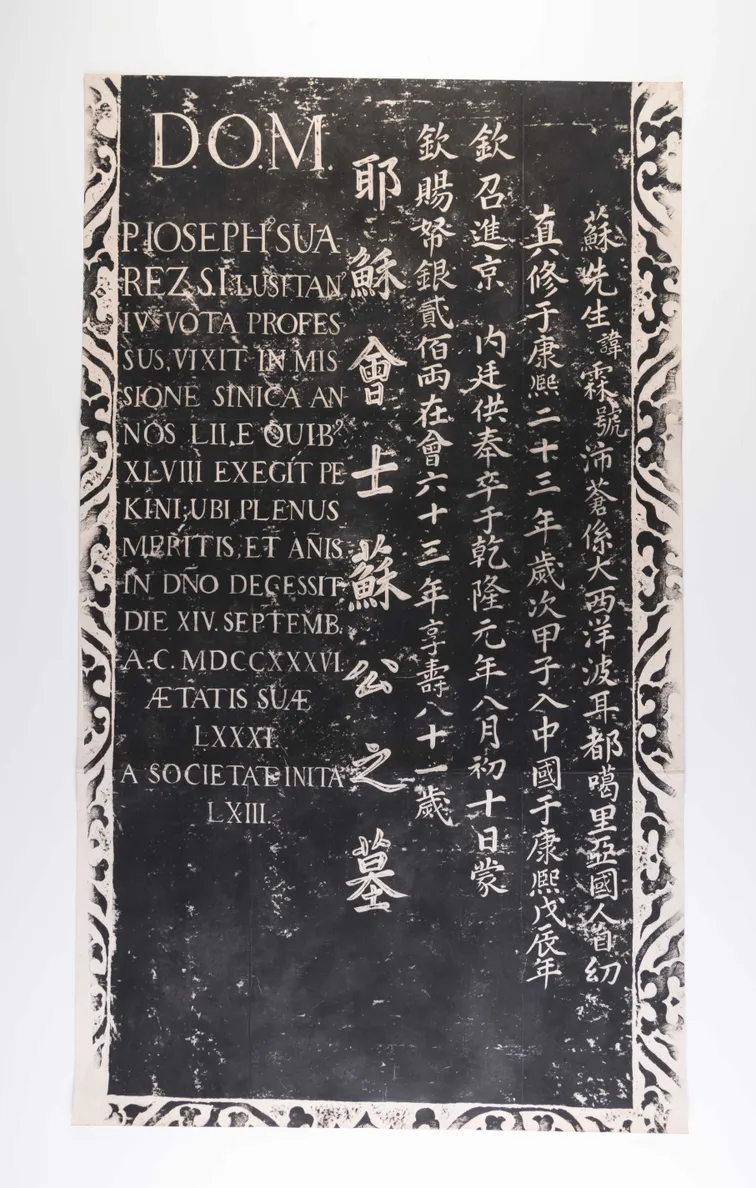

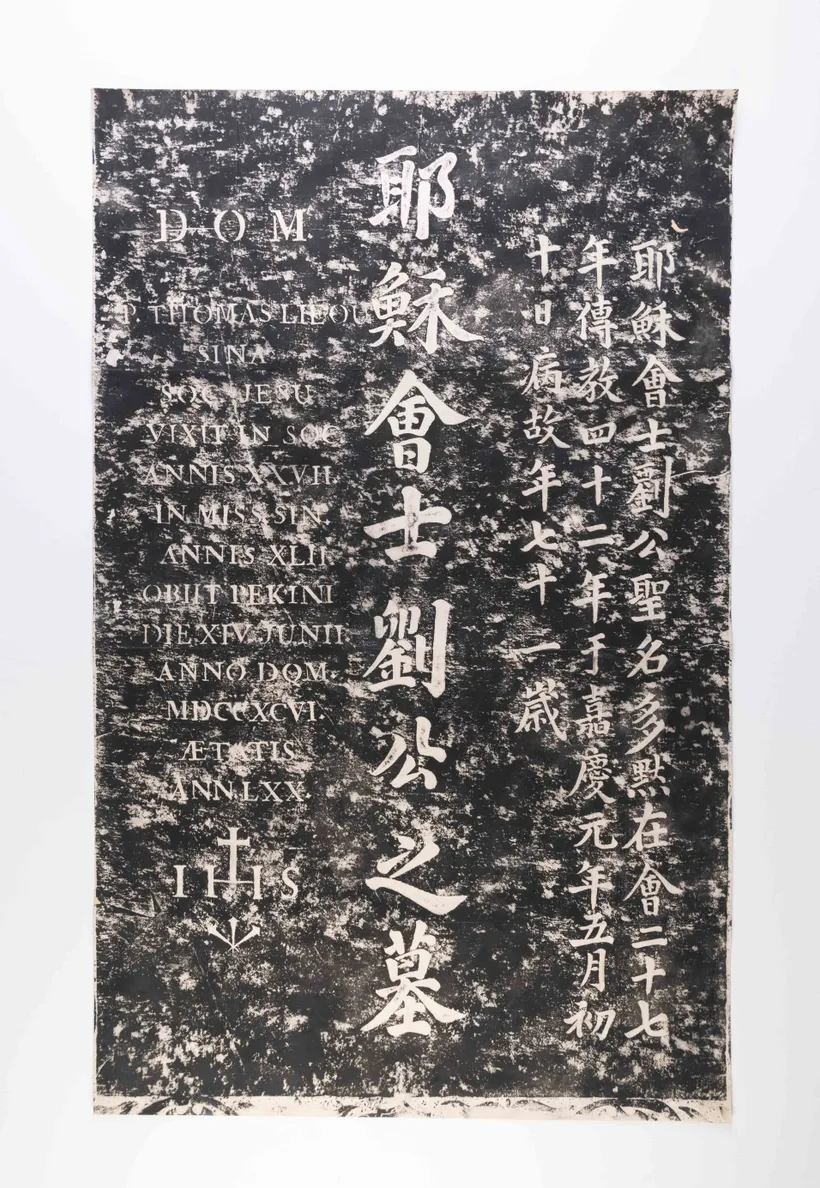

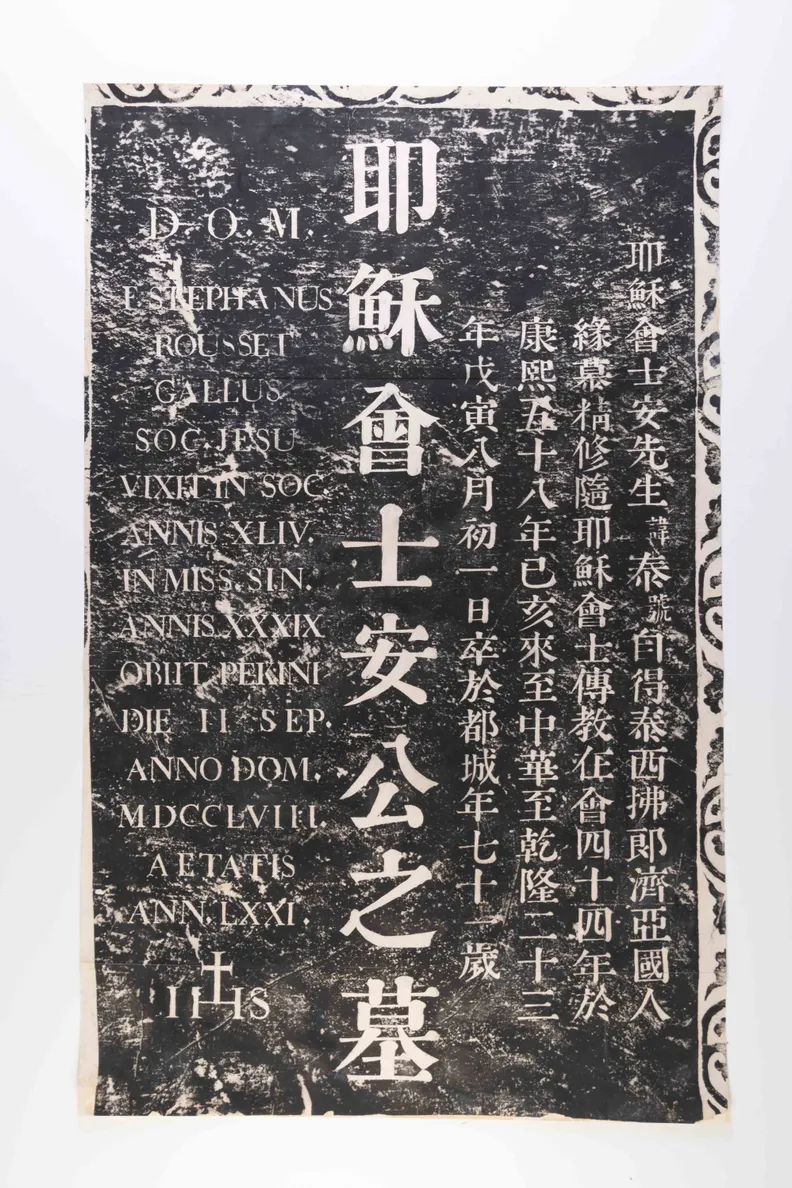

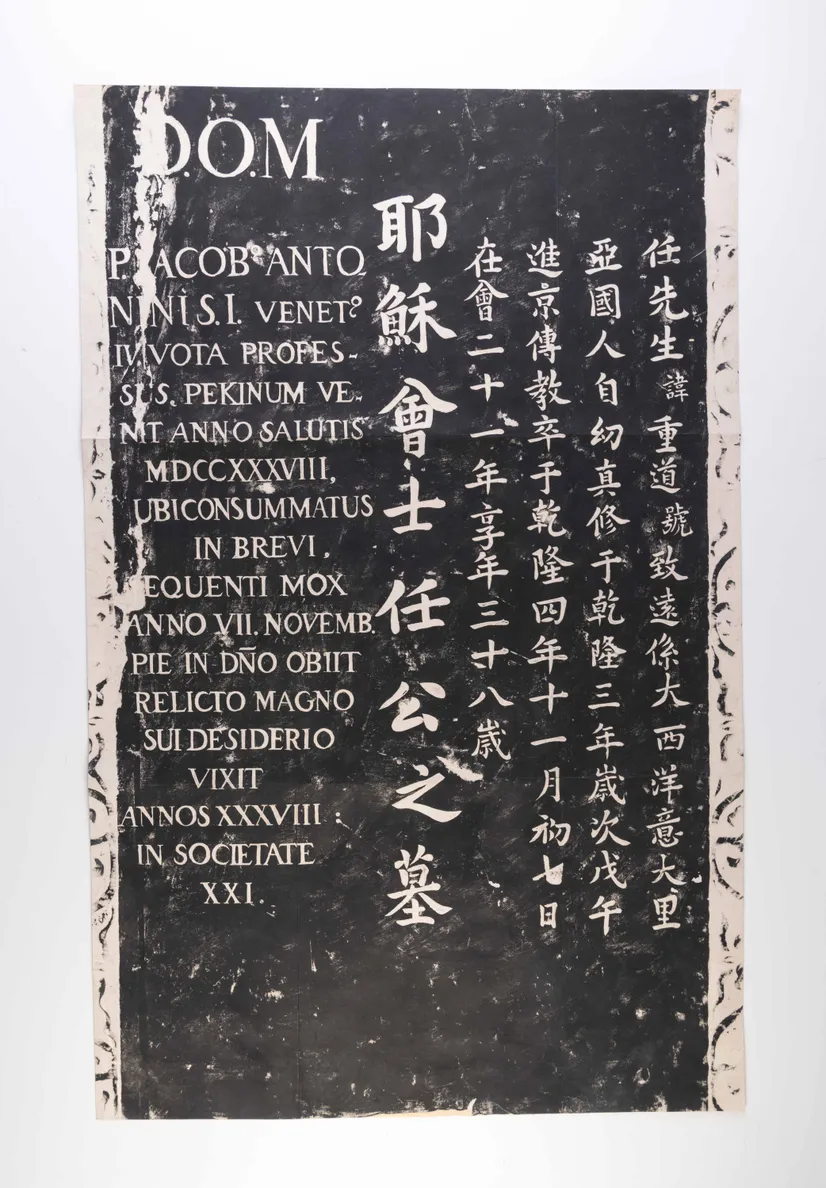

It is worth noting the graphic nature of the gravestone rubbings. The graves themselves were carved into white stone, which makes them difficult to read. One would be justified to compare them to a photographic negative, while the high-contrast nature of the print is the positive.

The Jesuits in China

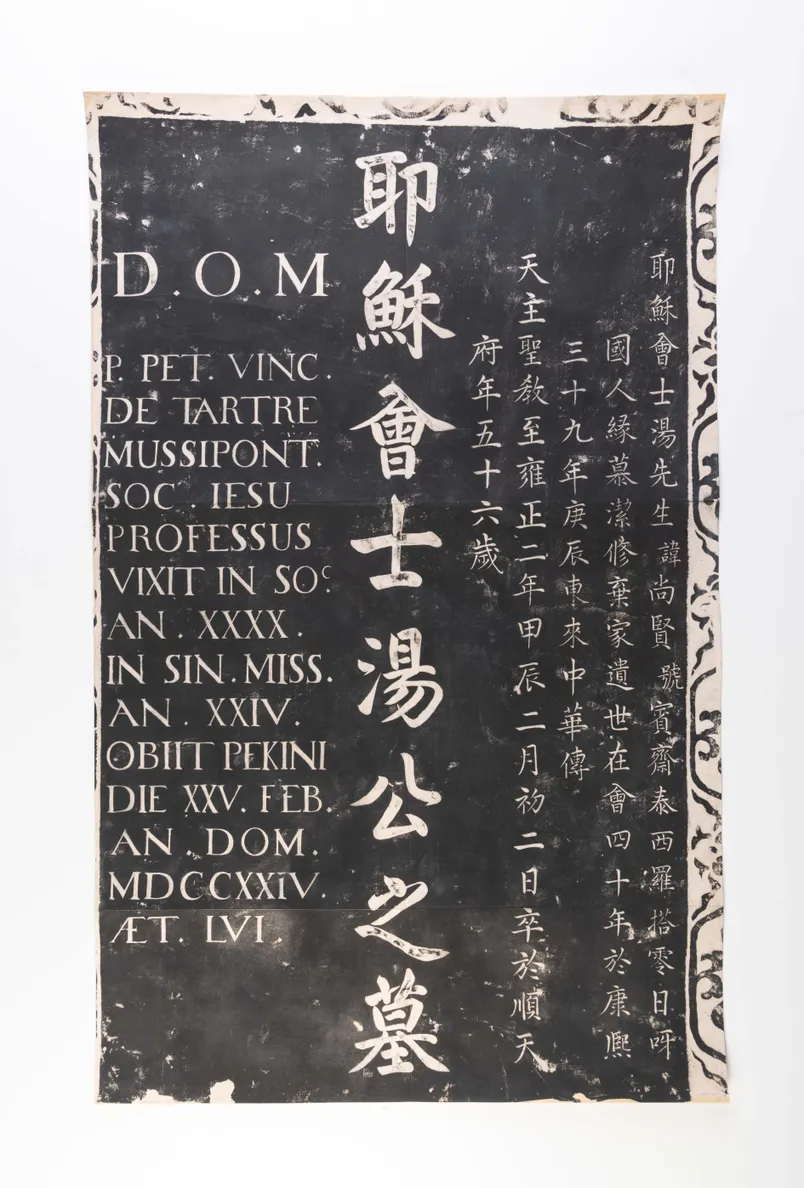

Founded by Ignatius of Loyola in 1540 the Jesuits focused on two main tasks, namely worldwide missionary work and education. They were part of the scientific revolution that swept Europe in the 16th century and were eager to embrace developments in mathematics, astronomy, physics and biology which established modern science. They rejected the monastic tradition of previous orders, organised themselves in seminaries, which were supervised from headquarters in Rome, and founded schools and colleges throughout Europe. Jesuits undertook a vow to go anywhere in the world in order to preach the conversion. In the 16th century, they founded missions in India, China, Japan, Ethiopia, as well as South America. They saw themselves as an international organisation with a global reach.

St. Francis Xavier was the first Jesuit to enter China and he died in Shangchuan island in 1552. The Italian Alessandro Valignano asked for competent missionaries to be sent from Goa: Michele Ruggieri arrived in Macau in 1579, followed by Matteo Ricci in 1582. Understanding that it was essential to learn Chinese and familiarize oneself with Chinese culture, Valignano founded St. Paul’s College, the first Jesuit University in Macau in 1594. After several failed attempts Ruggieri and Ricci were the first to be given permission to found a permanent mission in Zhaoqing, the seat of the Viceroy for Guangxi and Guangdong. There they published the first Chinese catechism and wrote the first Chinese-Portuguese dictionary. His knowledge in the field of science, in particular geography and astronomy, was reported to the Wanli Emperor (Ming) who finally asked him to enter the court at Peking in 1601.

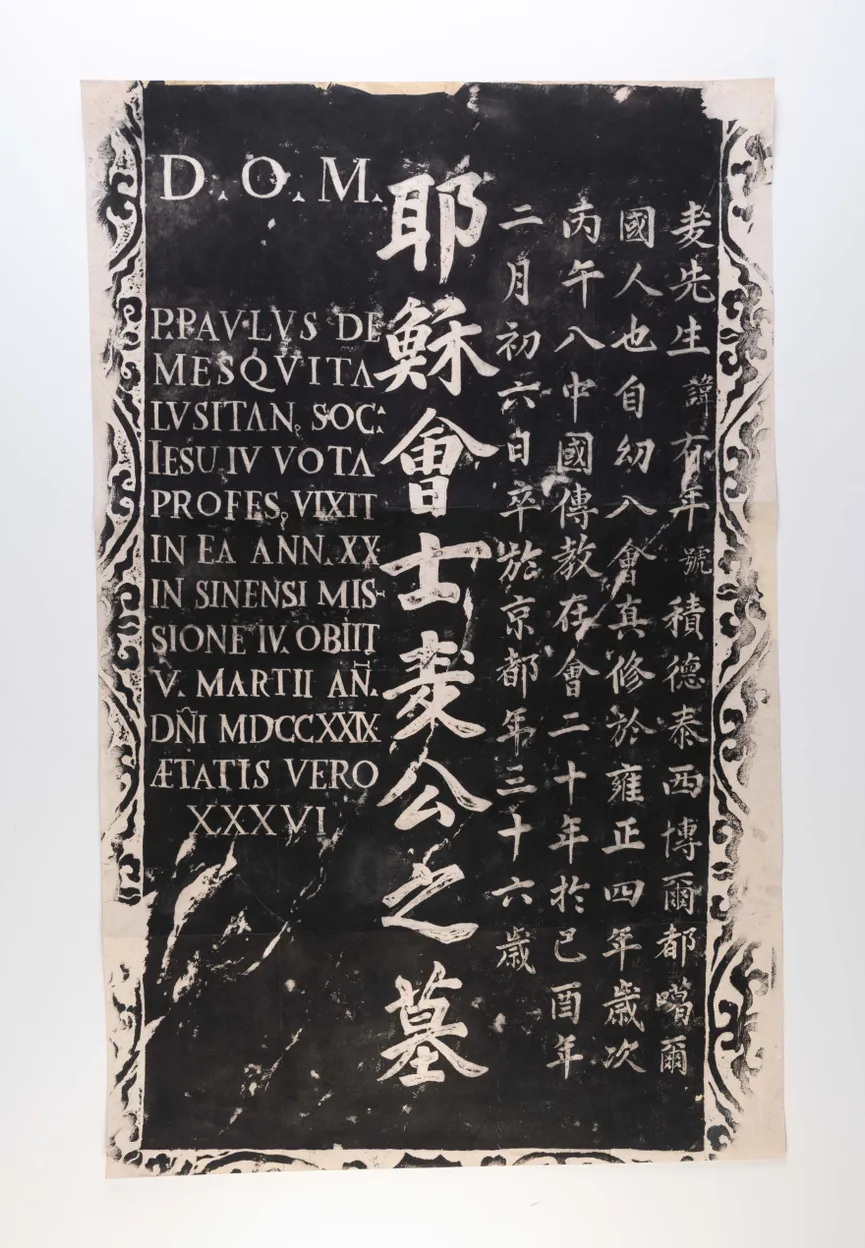

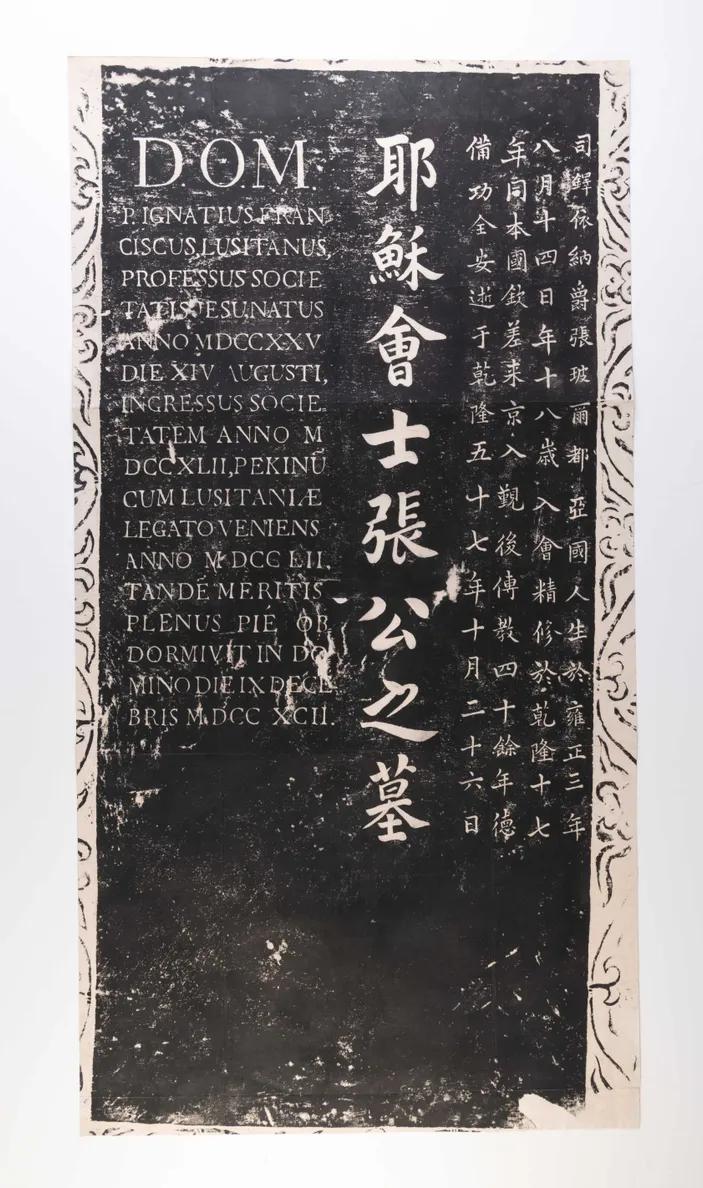

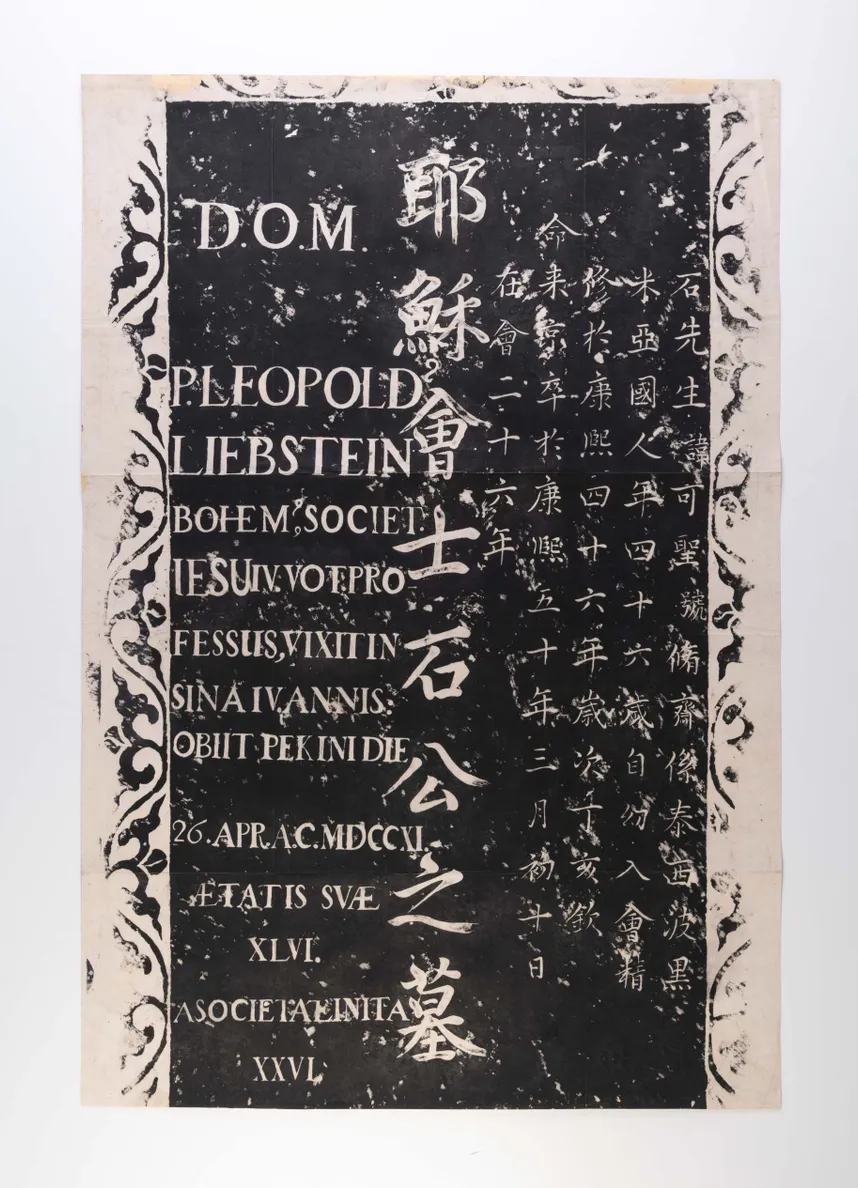

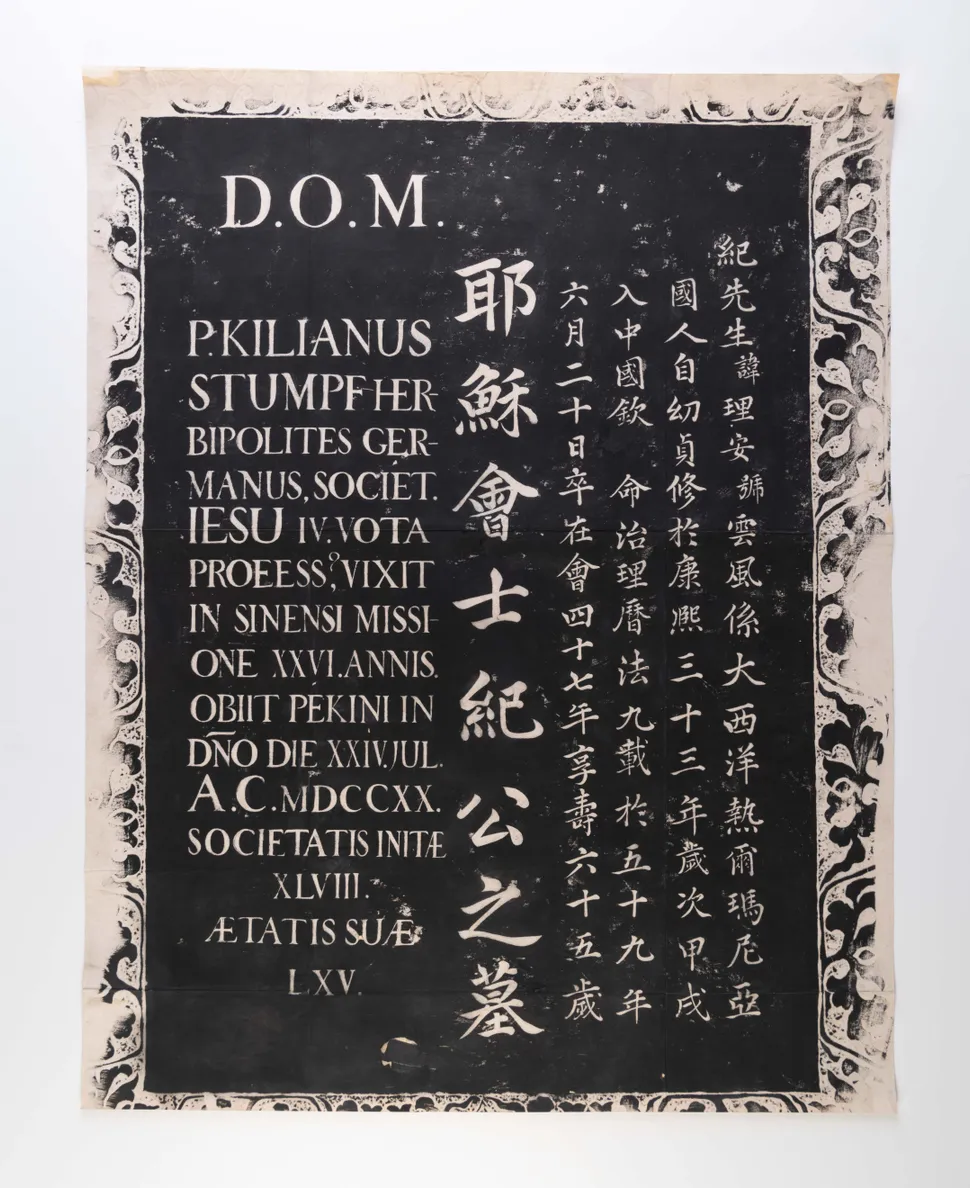

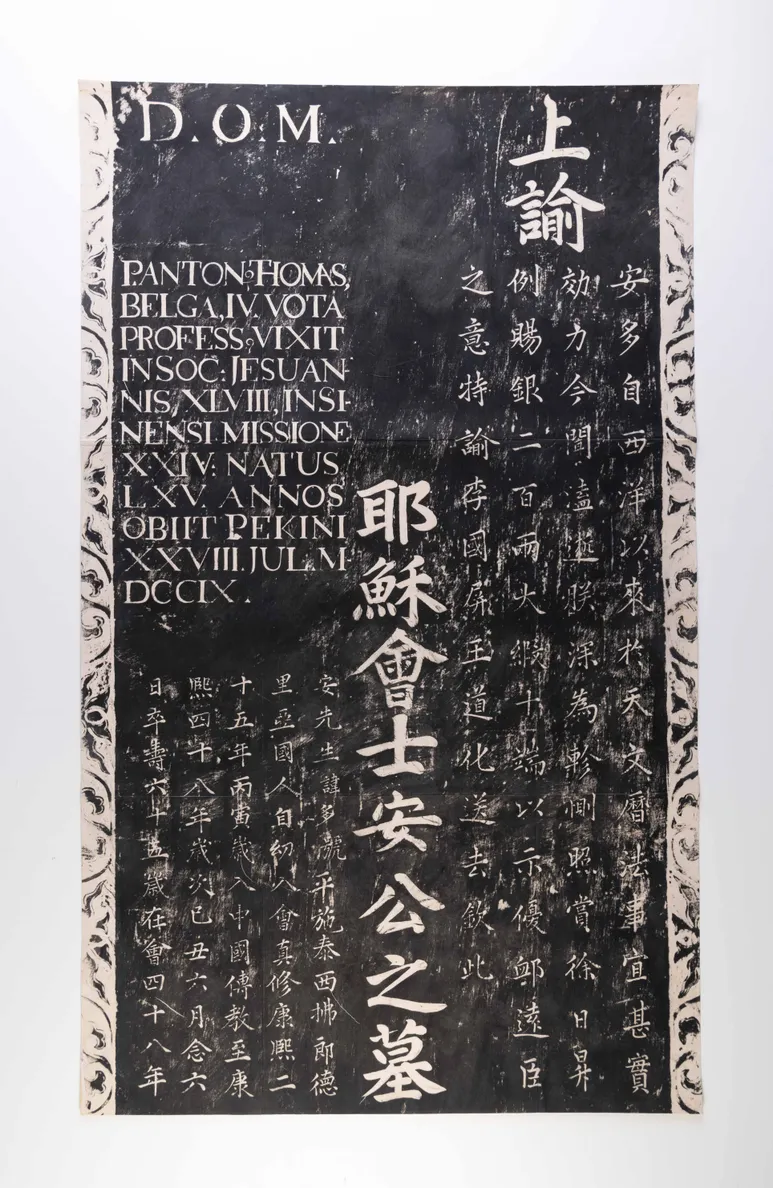

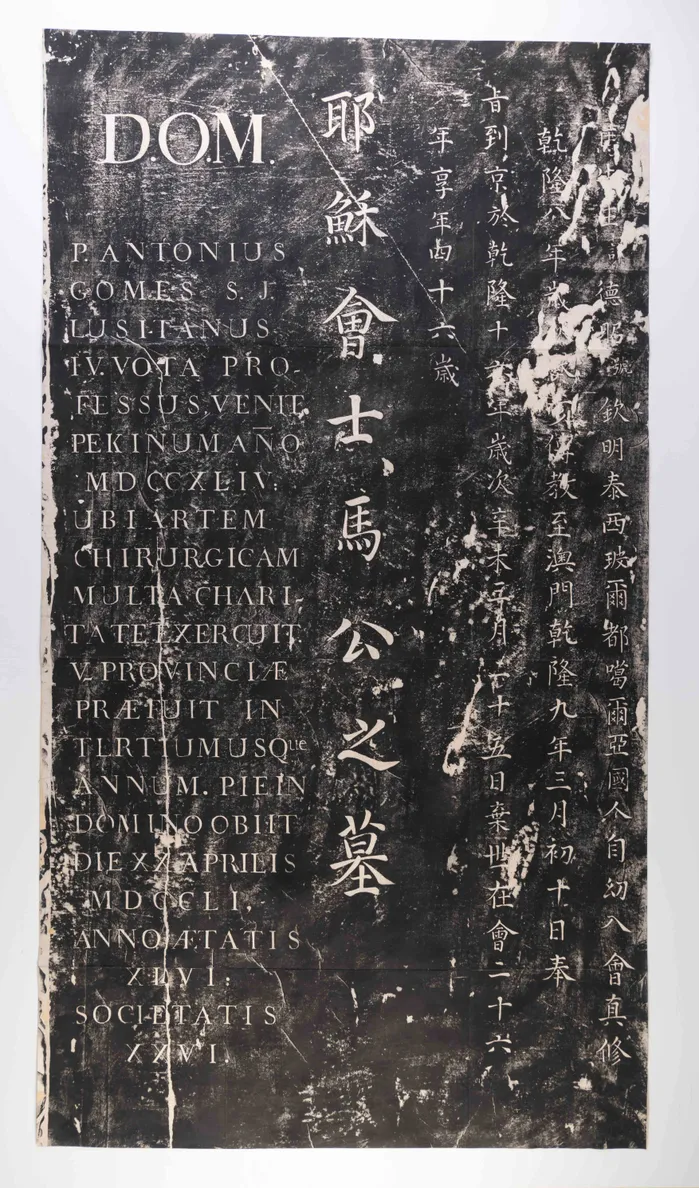

Jesuit grave-stones in Peking follow a particular pattern established in the Ming dynasty by that of Matteo Ricci. Their design is unique and exclusively used for Jesuit graves. On the left is the Latin text giving the name, nationality, summary biographical information (incl. the number of years at the China mission and the exact date of death, occupation etc.), on the right is the same text in Chinese and in the centre the large characters give their Chinese name and rank. Many of them carry the heading ‘D. O. M.’, three letters that stand for Domino, Optimo, Maximo (the Lord, the Best, the Greatest) a hidden motto not to be confused with a title of a church dignitary, or the designation for Benedictine and Carthusian monks.

Chinese ink rubbings are impressions on paper from low-relief or intaglio inscriptions and/or designs on stone (stele, pillars, cliffs, etc.), metal (bells, vessels, etc.), clay (pottery, brick, tile, clay sealing), bone, tortoise shells, and other hard materials. The production, use, and collection of rubbings have played a very significant part in the cultural pattern of China and some of her neighbours, especially Korea and Japan. In China particularly, with its strong historical tradition, rubbings have assumed an important role in the intellectual use of the country... In China the technique of making rubbings is considered quite special and is purely Chinese in origin. It has served as a type of camera for many centuries and is an ingenious and admirable one for it reproduces quite simply in full size every detail of the original surface. The technique is extremely useful and in no way damages the object being copied.

–– Hoshien Tchen: Preface to Walravens (editor): ‘Catalogue of Chinese Rubbings from the Field Museum’ 1981, p. xv.

Ink-imprints are commonly called rubbings or ink-squeezes. Because this is a duplicating technique on stone, it may be considered a prototype of lithography. In China, it is referred to as mo-ta ??. Instead of the stone being pressed on paper, however, the reverse is done - the paper is pressed on the stone. The traditional Chinese method is to moisten lightly a sheet of paper made from the cortex of the mulberry tree, or from bamboo pulp. This is a tissue-thin paper that is strong and highly absorbent. The moistened paper is then spread over the surface of the engraved object and gently forced into all the incised areas with a broad brush. A flat pad, generally made of loosely woven cloth with a piece of cotton tied inside, is then soaked with just the right amount of black ink and evenly tapped all over the paper. The higher surface which the pad has touched turns black while the incised part remains white. When the ink is dry, the paper is peeled off, giving a positive impression.

–– Tseng Yu-ho Ecke: ‘The Importance of Ink-Imprints’ in: Walravens (editor): ‘Catalogue of Chinese Rubbings from Field Museum’ 1981, p. xxv.

The Zhalan cemetary & the present collection

The history of the Zhalan cemetery in Peking is fascinating: The land was originally presented to the Jesuits by the Wanli Emperor as a burial place for Matteo Ricci alone. It was located to the west of the walled city outside Fucheng-men Gate and it also became known as the Portuguese cemetery (see Cordier). Gradually it was filled with other Jesuit graves and enlarged. During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 the graves were desecrated and many of the gravestones were severely damaged. In the mid 1950s most of the tombstones were moved to the Xibeiwang area and only the graves of Ricci, Schall von Bell, and Ferdinand Verbiest were kept in the original location. A Communist Party school for cadres replaced Maweigou church (which had been built in 1903) and an adjacent seminary, and the building now houses the Beijing Administration Institute. Deng Xiaoping approved the restoration of Ricci’s grave in the late 1970s and 60 gravestones were moved back to their original location.

Judging from the condition of the stone surfaces, the paper and the small manuscript tickets we can assume that the present copies were made before the Boxer Rebellion in the second half of the 19th century.

19 of the 20 rubbings can be located on Cordier’s map of the Zhalan Cemetery which shows the state of the graveyard before 1900 as well as the adjacent French cemetery. The only one missing is the grave of Mattaeus Lo (item 7). There are a number of un-attributed graves simply called ‘Sina’ in the French cemetery. Since Lo was affiliated with the French it is possible that he was not identified in Cordier’s map.

See: Cordier: Biblioteca Sinica. Vol. II, 1028-1036.